Making Makers: Reflections on (Many) Childhoods

This guest post is courtesy of AnnMarie Thomas, author of Making Makers: Kids, Tools, and the future of Innovation.

I’m always interested in hearing about the childhoods of people I admire. As a parent and professor, I can’t help but be curious about the experiences that have, in some part, made them who they are today. So many of the attributes I see in the Maker Movement – a willingness to learn new things, to collaborate, to help others, and an emphasis on process – are ones I wish for my daughters. Thus I set out, a few years ago, to collect stories from makers about what they were like as children. Over the course of more than 70 interviews I heard some amazing tales and realized that quite a few themes were emerging:

Makers are curious. They are explorers. They pursue projects that they personally find interesting.

Makers are playful. They often work on projects that show a sense of whimsy.

Makers are willing to take on risk. They aren’t afraid to try things that haven’t been done before.

Makers take on responsibility. They enjoy taking on projects that can help others.

Makers are persistent. They don’t give up easily.

Makers are resourceful. They look for materials and inspiration in unlikely places.

Makers share – their knowledge, their tools, and their support.

Makers are optimistic. They believe that they can make a difference in the world.

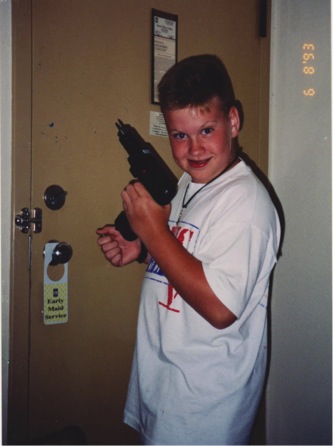

Not surprisingly, quite a few SparkFun employees ended up on my interview list. Dr. Lindsay Diamond, SparkFun’s Director of Education, and Nate Seidle, Sparkfun’s CEO, even shared some childhood pictures. So what were these two like as children? Below I share some excerpts from Making Makers: Kids, Tools, and the Future of Innovation (Maker Media, 2014).

Taking (Unexpected) Things Apart

When the Maker Movement is brought up in education conferences, I’ve seen that many people assume that all makers were avid “take apart”-ers as kids. While many makers I spoke to did enjoy taking things apart, many others didn’t, preferring instead to read, play outdoors, or explore other pursuits. In other cases, some young makers did enjoy taking systems apart, but not necessarily the sort of things you might expect.

Dr. Lindsay Levkoff Diamond, director of education at SparkFun Electronics, immediately answered yes when I asked her about this aspect of growing up. I began to imagine toasters and VCRs strewn about, but she quickly explained that, growing up in Florida, they had “an unbelievably large population of lizards. They were already deceased. I would take sticks and try to see what was inside.” Lindsay’s take-apart subjects included “all things biological,” both plant and animal-based. Flashing forward twenty some years, Lindsay is now a champion of open source education, particularly as it relates to electronics. Whether it’s lizards or flashlights, Lindsay is among those educators promoting the importance of letting kids follow their curiosity.

Open Source from an Early Age

In high school, Nathan Seidle had a fancy graphing calculator. Given that he was a talented mathematics student with a strong interest in computers, it’s not surprising that he wanted to find a way to connect his calculator to his computer. Such cables were commercially available, but they weren’t cheap. So Nathan went on a BBS (bulletin board system, a type of online message system that was popular in the 1980s and 90s) and started looking for information on how to make such a cable. He found a schematic online, which he used to build a functioning cable (which is particularly impressive when you consider that the BBS was text-based, and so was the schematic). This was the first project of this type that Nathan had undertaken, so he didn’t even know where to buy the parts. Other posters on the BBS advised him to buy them at RadioShack, which he did, thus beginning a small business of building and selling these cables to his friends at a price much cheaper than the commercial rate (when I asked if the cables worked, Nathan’s reply was an enthusiastic, “A few of them did!”). While making his first cable, he accidentally got solder on two of the connector’s pins. He used a box knife to remedy this and ended up cutting himself, leaving a scar. Now he looks back and thinks, “that’s the scar that started SparkFun.”

Perhaps the biggest lesson I was able to take away from these discussions is that while there were many similarities that popped up among the stories, every maker I spoke to had their own unique path that they followed. We, as parents and mentors, don’t always need to have all of the answers. Our support can be sufficient. Allowing children, and the children-at-heart, to explore their own interests, and empowering them to figure out how to make their ideas come to life, are some of the best ways to help them define success for themselves.