Designing a control system for a robot battle arena

This post highlights my method of creating the control system for our AVC battle arena.

If you made it to AVC this year, you probably got a chance to see some robot fighting! Our arena had locking doors, LED lighting, hazards, big 7-segment displays and a control panel. If you didn't make it out to the event, skip through the recorded feed (Sparkfun AVC 2015 Recored stream, 38:27) to see the arena in action.

I volunteered to help run the battle arena. Unbeknown to me at the time, this also volunteered me to help build the battle arena – not that I had any objection. This post shows the process that went on in order to develop the control system.

Initial Specification

Our resident battling robot expert Casey was buying parts and attaching LED strips to the arena in the weeks leading up to the event. Being a maker I wanted to help out, but I had no idea what the master plan inside Casey's head was. On the Monday before AVC the arena was coming together, so I asked Casey, "So...how is this stuff going to be controlled?"

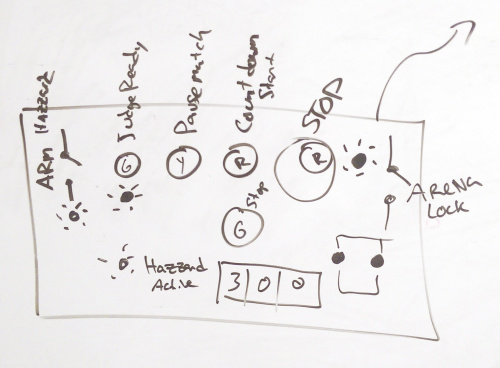

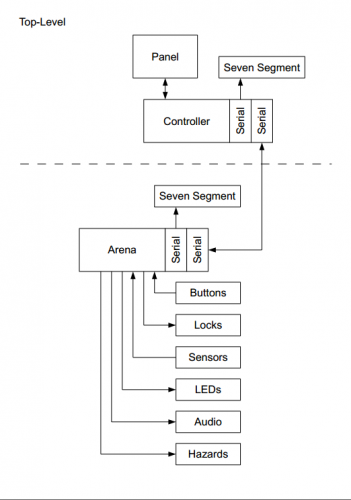

And he drew me this:

After a bit of conversation, I found out that the arena and its switches, LEDs, buttons and hazards would be driven by a microcontroller, and that the judges would control the thing through a panel. We decided that it was probably not the best idea to run bundles of parallel wires from the arena to the panel, and that we could send serial and transfer the complexity into code. We agreed on a topology where the arena would control all the peripherals, and the controller would be basically dumb, and function as an IO unit for the arena.

Building the panel

My conversation wtih Casey was very brief and my knowledge on battle arenas is quite limited so I decided to lay out a panel and show it to the customer (Casey).

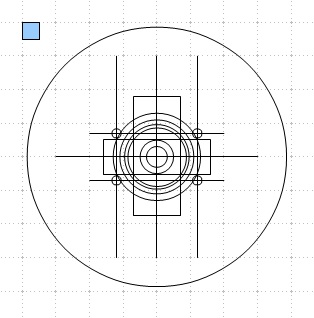

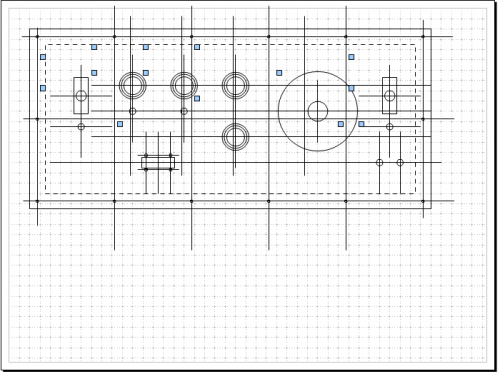

First, I gathered all my materials from our warehouse and measured them. Then I created a 'master' shape layout using OpenOffice Draw, a surprisingly useful (yet aggravating) vector tool.

Then I drew the thing out, making use-case assumptions about button spacing and layout.

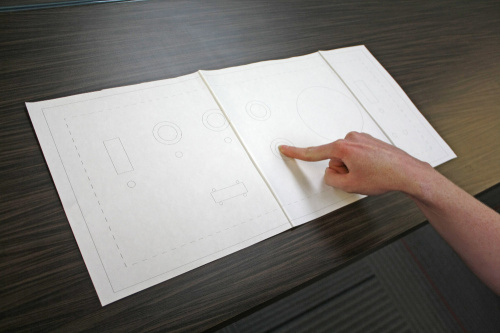

The next step was to show the customer. This brought to light exactly how big that giant e-stop button really is, and gave a sense of proportion.

After Casey verbally signed off on the prototype it was down to our Epilog laser cutter. I cut the shape, built a 1x4 box for the edges and assembled the panel. Last minute I decided to try combining raster etching with cutting in the same print job, which was a mistake. Because the model didn't have text, no one reviewed the design and the "TAP-OUT" section was mislabled – it should have been labeled "COUNT-OUT."

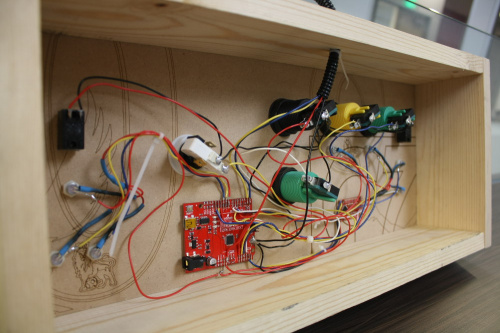

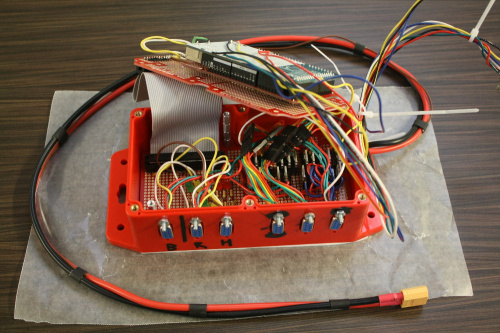

Electrical assembly was very straightforward. Wires were attached to the buttons, the RedBoard was sticky-foam-taped down, and wires attached as orderly as possible in the chaos of proto-development.

Programming

High-Level Topology

This was the first time I'd ever created a battle arena for robots, so the function was completely foreign to me. From what I've seen on TV I knew there was a match time limit and, at some point, the hazards turned on. Instead, I started by drawing a top-level diagram of how the electronic systems operated, to the best of my knowledge (if I don't know how something will be, I generalize – when starting it's much more important to draw a box with a "?" in it than to get bogged down and do nothing).

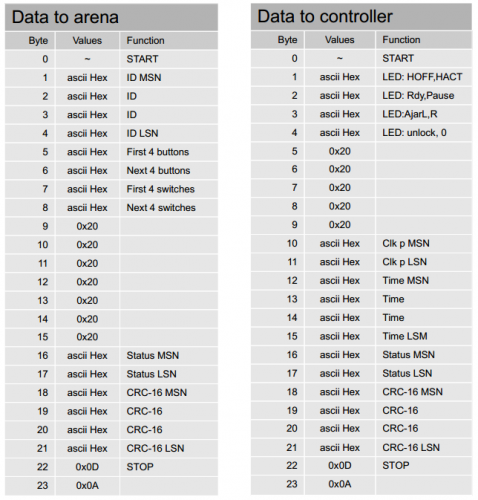

At this stage we had a classic "A magically connects to B" scenario. Using the knowledge that Arduino serial streams like to be ASCII oriented, I developed a system of using ASCII alphanumeric representations of raw data on the serial stream, rather than trying to send raw data. Actually I used code from the Teensy 3.1 XBee Adapter GitHub that I had previously written to jockey button data over wireless in a simple ASCII packet. I wouldn't have been able to complete this project in time without re-using code I previously developed.

To ensure I wouldn't code myself into a hole, I specified the format of these ASCII packets in a document.

Here's an example of a packet I sent to the controller in order to test the functions:

~9555 A432100BEEF

Controller-Side Design

The controller had two main functions:

- When a button changed, it sent the packet

- If a packet came in, it changed the LED and 7-segment states

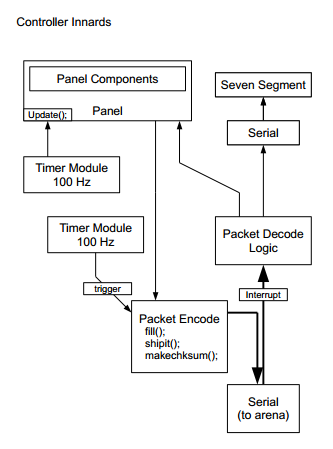

Now came the real work. I needed to answer the question, "How do I make the program?" Again, I drew generally. I knew there was a serial stream that drove the 7-segment displays, so I just made a box with "Serial" in it (this could be SPI, I2C, or UART, I don't really care). It solved that problem in my mind though, so I drew it and moved on.

(I ended up driving the 7-segment with I2C.)

Having drawn the document, I knew what modules I would be bolting together to make the thing work. They were:

- Panel -- a basic container for panel components

- PanelComponents -- definition of panel LEDs, buttons, knobs (none in this project) and switches

- timerModule -- a class that generated a sort of call-back, sourced from an interrupt-driven timer

- 7-Segment Serial Display drivers -- Implanted into the main sketch

- Packet driver from the Teensy 3.1 XBee Adapter -- implemented into the main sketch

Basically, these were all things I've used before in other projects. Programming became an excercise in making up new names for all the objects, as well as ironing out code I never thought would see the light of day again.

One thing I did have to code fresh was the LED drivers. I already had the panel components included but never needed the LED object. I duplicated a button to start with and coded it to display on, off, or flashing. All LEDs inside the same panel were tied to the same flash signal, so when a group of buttons were set to flash, they flashed in unison! Things like this make me happy, as well as serve to grow my collection of code snippets.

Arena side design

While I was developing these systems, Casey was busy shifting the low-level microcontroller signals to higher voltage and current levels to drive the systems of the arena.

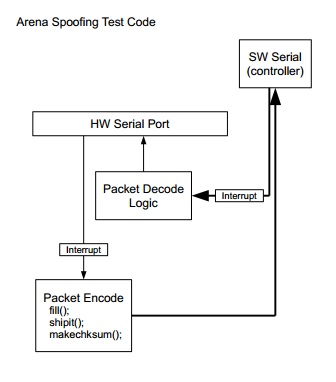

I didn't have access to that box or to the specifics of how the peripherals were attached, so I had to make do with a dummy arena, consisting of an Atmega 328p RedBoard with a serial link. This was a situation where I had absolutely no idea what the target was going to be, but I had to work anyway. I developed a topology that showed the elements I knew would exist, and worked from there.

From the diagram, you can see that that the program interfaced the serial monitor port of the development computer and the controller. Now that I had working controller code in hand, I re-used the packet logic directly and had decently quick success in getting this implementation to operate.

The challenge of writing the code for the arena was the state machine that made the arena operate as the battling game. I really thought of this system as the type of thing you would expect from an arcade game, partly because it used arcade buttons, but more because the UI was very call-and-response oriented. I did a thing; the arena responds.

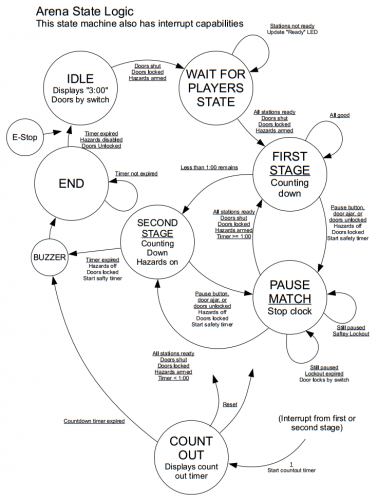

Using the basic ideas I talked about in my last post, State Machines: blink.ino learns to snooze, I guessed at a state machine that would operate as Casey and I had been talking about.

Now, this is a super odd state diagram. I've noted that this state machine also has interrupt capabilities, it's not 100% defined, and there are a few states just hanging out or not directed back to anywhere in particular. For instance, I knew the E-Stop button should drop everything and go back to idle. Well, I knew there needed to be an E-Stop function, but I wasn't really sure where it would go. There's a buzzer state yet the arena had no buzzer, so that was dropped. Again, it was a case where I wasn't ready to plow into code but I needed to mark down some of my ideas, and this state diagram was the result.

Truth be told, I think the "Second Stage" was dropped altogether. I went through three iterations with Casey where I ran the code and asked him, "Is this how it's supposed to act?" I never got lost working on the first iteration because I had a map, and it wasn't very difficult to modify the operation after the base state machine was functional.

When the arena controller was complete, Casey passed me off a list of IO pins. I hooked them into the code, targeted the Mega rather than the Uno, re-mapped the SoftSerial to a spare hardware UART, and the code ran. I didn't even have to change my interrupt routines; the port naming convention is standard between the two microcontrollers.

Finally, here are the modules that were rolled into the arena controller's code:

- Panel -- a basic container for panel component

- PanelComponents -- used for the player buttons

- timerModule -- a class that generated a sort of call-back sourced from an interrupt-driven timer

- Large Digit Driver modified drivers -- these large 7-segment displays are really cool

- Packet driver from freshly completed controller -- implemented into the main sketch

- Arena state machine -- class containing the state machine logic

Lessons Learned

Plan for code re-use -- You never know when a project you're working on will need a piece you've previously used. Writing modulular code and keeping it maintained in a working project folder will allow you to save time and effort over and over again. My timerModule class makes it into pretty much any project I do, to the extent that I ported it to Teensy and now maintain that too.

Document a plan for development -- I never felt bogged down with that uneasy feeling that I'm just digging myself in when working. I always had a target and that kept me sane. (Ok, I dug myself in a bit around the 4 a.m. hour Friday night, but I don't have clear documentation for that part of the project so it's no surprise.)

Proof your text with the customer -- Save yourself the embarrassment.

Check your fonts -- When using CAD software with fonts, make sure the fonts are identical to the ones on the computer that is going to be doing the control. This actually comes up now and again with PCB layout. Sometimes the way our computers render the boards is different from the fab house. Sometimes the difference is a short circuit.

Don't ask Casey if he needs any help -- I lied, I would ask him again twice over.

Conclusion

There's a couple kinds of "making" in my mind. There's "making to accomplish," and "making just to see if you can." The latter seems a bit useless, but all the things I discovered while just trying things out for fun became the building blocks when it was time to make for accomplishment. The panel construction method, code modules, documentation – and basically everything – were a re-use from previous projects.

The entire time I was writing this post I debated releasing the code (rather, telling you the location of the open-source code). I decided to allow it into the wild with the following disclaimer.

Disclaimer: The following repository has not been polished since AVC, and may not be until Casey gets a new chamber that needs a controller, at which point this disclaimer will be removed.

Happy making!

Marshall