Summer of Tariffs

The impact of managing uncertainty with a catalog of 2,400 storefront SKUs

This is the first in a short series of blog posts about the impact of the July 6 tariffs on SparkFun's business.

For SparkFun, the story of tariffs is a story about managing uncertainty, and doing everything we can to keep losses to a minimum as we transition from 1-5 percent to 25 percent tariffs on a significant number of our components. For us, it’s not a story about manufacturing in America, or the threat of recession, our current president or China’s increasing global influence.

Today, this story is about the short term: the three or six or nine months it will take for our business to fully transition to a massive increase on our cost of goods. Ultimately, we will have to pass the cost on to our customers in some way, shape or form, but the challenge we face is how much, when and who.

Getting an answer to the question of how much we should raise prices in response to the increase in our cost of goods is a big, hairy, intricate problem to solve with seemingly infinite dependencies. This blog post is about how SparkFun’s business works within an incredibly complex global market, and the huge task of managing the chain of uncertainty imposed by these new tariffs.

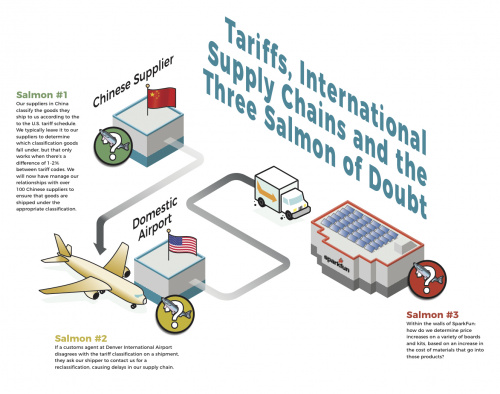

How Tariffs Work

Tariffs are applied by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents at the ports where a shipment enters the United States. For us, that’s Denver International Airport. We get most of our shipments by air, since our orders are rarely the size and weight that would make ocean transport more cost efficient (thanks to all the small parts and pieces we order in small quantities). Each item falls into a certain classification as published in the U.S. International Trade Commission’s Harmonized Tariff Schedule, and their handy little search tool helps businesses like ours look up those classifications and determine the tariffs imposed on those goods.

When goods from suppliers arrive in port, the customs agent applies tariffs through our international shipper based on the classifications our suppliers list on the commercial invoice for that shipment. Our suppliers include the U.S. classification in the bill of lading based on their knowledge of U.S. tariff schedules. We pay tariffs through our international shipper when we are billed by them.

Occasionally, our suppliers don’t include the right classification for the goods they ship to us. When that happens, a customs agent calls our shipper, who then calls us at SparkFun to either verify the classification or provide a new one.

In an era when discrepancies in tariff charges between classifications amount to only 1 or 2 percent difference, we can afford to rely on our supplier’s judgment to classify goods properly. Now that the tariffs represent 25 percent on some goods, proper classification becomes a larger compliance and due diligence issue, as U.S. Customs and Border Protection increases the level of scrutiny to prevent companies from evading new tariff costs. For SparkFun, this means a significant increase in the time spent checking supplier classification of goods.

An additional uncertainty also lies in any discrepancies between how SparkFun anticipates its products will be classified and how our suppliers, shippers and customs agents classify them. This is more of a planning problem as we start to assess and project costs as a result of tariffs into the future.

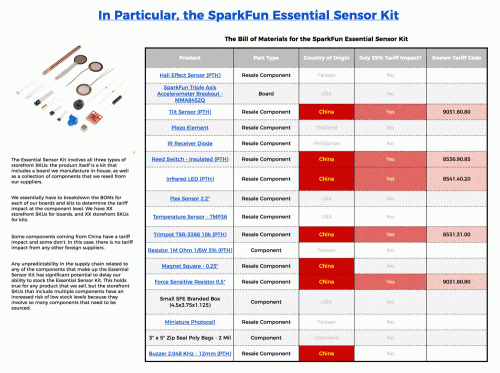

Journey of the SparkFun Essential Sensor Kit

To illustrate the complexities of price increases based on an increase in our cost of goods, we'll outline the journey of the Essential Sensor Kit to the SparkFun storefront. If our task was to manage an increase in the tariff on a single product, we could simply match the increase in price to the increased cost of that product. However, our storefront SKUs fall into roughly three categories: board, kit and resale.

A board refers to the storefront products we manufacture in house from raw materials or components we’ve sourced from suppliers all over the world.

A kit refers to a storefront product that includes a collection of different parts bundled together, some we buy and some we build.

A resale product refers to component or product that we resell without any alteration. Most of our components and small parts are classified as resale, meaning that we order them from suppliers and then sell them on our storefront to our customers in the same form they came from suppliers, like LEDs.

Our Essential Sensor Kit includes a combination of boards and resale products, which makes it a great candidate to share how a single tariff, or a combination of multiple tariffs, can be a problem greatly amplified when managing a catalog like ours.

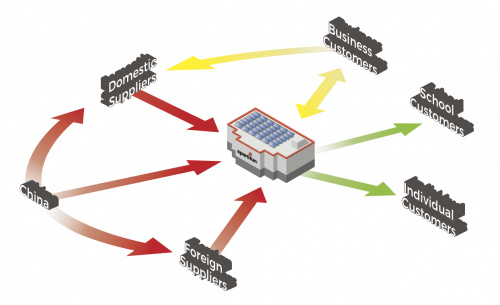

Complexity of Our Business

To top it all off, SparkFun isn’t just an e-commerce company. It’s also a supplier to other companies like Digi-Key, Mouser and Arrow, as well as a distributor of goods like Arduino, Raspberry Pi and micro:bit. We also manufacture goods in-house, and sell both online and to business partners like Intel, IBM or Microsoft. On top of that, we work closely with schools to stock their classrooms with low-cost, well-documented product that can be used to teach kids how to write code and build STEM skills.

So when we get calls from our distributors, or calls from school districts worried about price increases, we can’t provide a concrete answer right now because of the complexity of our supplier-distributor marketplace. We essentially have to manage two types of amplified cost impact:

- Product & Inventory: The increase in cost of boards and kits based on tariffs on individual goods.

- Supplier & Distributor: The increase in cost from domestic suppliers whose goods include components with a Chinese country of origin, and the price we have to pass along to our distributors.

Challenges

For many small businesses like SparkFun, the challenge of managing the impact of increased tariffs ultimately comes down to resources. Large companies in our market have the resources to deploy lobbyists and legal experts to either fight the tariffs or discover loopholes, as well as sophisticated supply chain management teams that work closely with suppliers to optimize their cost of goods.

We also have to consider the opportunity costs associated with managing this change. From a supply chain perspective, if we allocate our resources to determining the impact of tariffs, we’re not spending that time managing the challenges of the current driver shortage for ground shipping, or looking for ways to manage fuel surcharges. Perhaps most importantly, we’re taking resources away from managing supplier relationships, sourcing the most cost-competitive goods while preserving quality, and managing inventory and stock levels in an increasingly competitive and unpredictable supply chain landscape that results in more expensive goods (tariffs aside) and longer lead times. This impacts our customer when we can’t keep certain products in stock, or they cost more due to materials shortages or competition from larger companies that buy up the global supply.

All of the points of uncertainty explained above are only exacerbated when managing a catalog of 2,400 storefront SKUs, and the 4,000 small parts that go into those products, for customers as varied as the individual engineer, K12 teachers and university professors, corporate partners, and distributors.

Do we have concerns about how this will affect our customers? Absolutely. We’re concerned about teachers with limited budgets and about the way our competition will price the same product. We’re concerned with continuing to be a compelling and competitive option to engineers who use our products to prototype. We’re concerned about an already challenging pricing landscape in electronics, and we hope our customers are willing to take this journey with us and not let price variability in the near term prevent them from bringing their project ideas to life.

While we’re tempted to make sweeping statements about how this is good or bad for our business in the long term, the only thing we know is that in the short term, this certainly isn’t good for business. The problem for small businesses like SparkFun isn’t necessarily an increase in tariffs, it’s managing the uncertainty around it and not only keeping our losses to a minimum, but being able to confidently quantify those losses in the first place.

Ultimately, the answer we have to give about how tariffs are impacting our business and our customers is the same as the answer we are getting from our suppliers and partners: “We’re not sure. We’re still evaluating.”