Enginursday: Fixing the ESP32 Thing Plus

In this Enginursday post, we talk about a fixing a problem the ESP32 Thing Plus had.

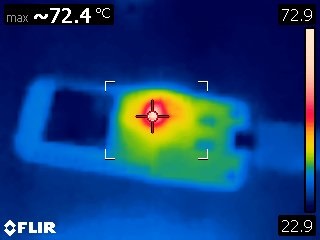

Recently, we released v20 of the ESP32 Thing Plus board. After releasing v10, we received some feedback that some boards weren’t able to upload code and the CP2102 was getting hot. It wasn’t a widespread problem, but it was a consistent problem for people that had the issue. When I was testing the board for example, I was able to upload code using both the USB ports on the computer, as well as my powered USB hub without issue. The USB power adapters didn’t cause any problems for me, except one, which helped figure out what was causing the problem.

The problem was a result of inrush current, specifically with switch mode power supplies. Switch mode power supplies have soared in popularity because they allow for smaller and more efficient power supplies, and can be found in nearly all electronics from phone chargers to desktop computers. They achieve this by increasing the AC frequency, which allows the transformers to be smaller by switching at a higher frequency, and by using a buck converter, they switch current through an inductor to charge a capacitor to a specific voltage.

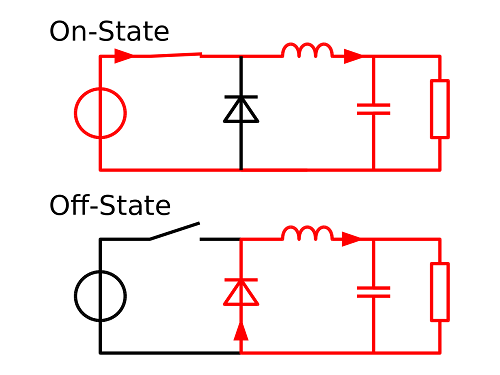

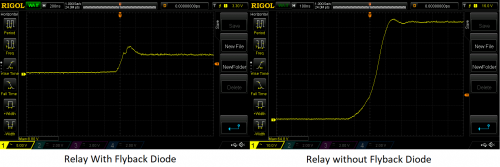

Without diving too much into the theory, inductors store energy in a magnetic field and resist the change in current. When an inductor sees a change in current, it tries to maintain that current by increasing the voltage until they run out of energy. This is why in our relay boards we use a diode across the coil to limit flyback voltage spikes, which could cause damage the switching transistor, as shown below.

Finding the problem

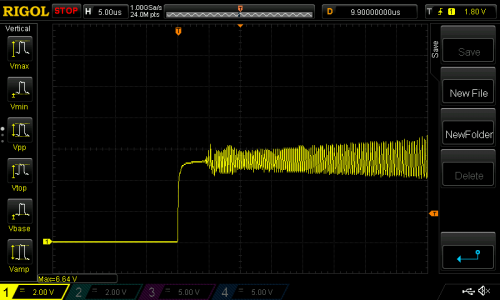

Back to the ESP32 Thing Plus though. Now that I had a power supply that was able to replicate the problem some of the users were experiencing, I was able to connect my oscilloscope to the VBUS pin to see what was happening:

After seeing the peak voltage of 8.24V, I went back to the datasheet for the CP2102 and saw that the absolute maximum input voltage on VBUS was 5.8V. I performed the same test with a linear power supply, which still had a small overshoot, but at only 5.68V it was at least below the limit:

I suspected the problem was a result of inrush current and I turned my attention to the ceramic capacitors, which have a low equivalent series resistance (which you can learn more about here). Having a small ESR value is good because it allows the capacitor to respond quickly to voltage ripple, but when it first charges up it can cause a large initial spike in current. At first it might be tempting to just remove capacitors, but as the waveform below shows, without capacitors the ripple from the switching power supply would generate too much high frequency noise on the VBUS rail.

Without the capacitors though, we can see that the initial voltage spike is gone. Knowing that the low ESR capacitors are causing a problem but that removing capacitors creates a new problem, I needed to find the middle ground, which can done by adding intentionally adding ESR to capacitors with a small value resistor in series with the capacitor. Another problem, however, is that because of where the capacitors are placed, adding a series resistor to the capacitors would add a lot of time reworking the board to move traces and vias.

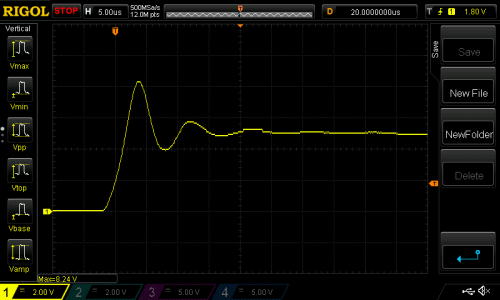

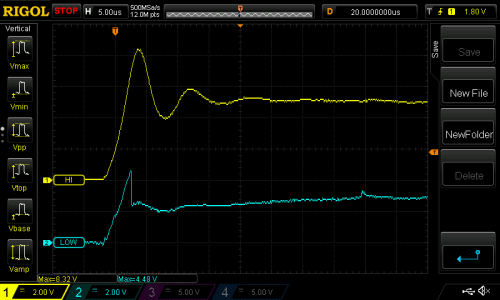

Before investing the time moving traces around, there was more room available around the CP2102, which gave me another idea. After checking with the datasheet again to see that the input current for the CP2102 was around 20mA during normal operation, I wanted to see if adding a resistor in series between VBUS and the supply pins of the IC could fix the problem. After using my decade resistance box, I settled on value of 10 ohms, which produced the following result:

The yellow trace is on the high side of the resistor connected to VBUS, and the blue trace is connected to the low side of the resistor connected to the supply pins of the CP2102. As you can see, the spike still makes it through the resistor, but instead of reaching a peak voltage of 8.3V it only peaks at 4.48V. The time scale of 5us/div makes it look like the CP2102 drops back down to around 3V and stays there, but the actual voltage drop with this supply is around 200mV and gets to a steady state voltage within 200us.

As engineers, the goal is to have a test procedure that can thoroughly test your design to identify limits and fix them before it lands in the hands of customers. But just like when the Raspberry Pi added USB-C, mistakes can still happen when you use components for the first time.