NASA's Mars Ingenuity Helicopter Ends its Mission, but This is Just the Beginning

After three amazing years, and with parts purchased straight from SparkFun, the Mars Ingenuity Helicopter makes its final flight.

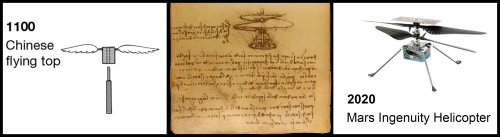

People have been captivated by the idea of helicopter flight for centuries. A craft that would allow one not only to fly through the air like a hawk, but also to hover, stationary, like a bumblebee. Italian multipotentialite (or polymath, if you prefer) Leonardo da Vinci drew his design for the “aerial screw” way back in the 1480s. The concept itself can actually be traced back even further to the Chinese flying top, circa 1100.

It would take almost five centuries before flight in a craft with horizontal rotors would become a reality, and thanks to their ability to take off and land vertically, as well as hover in place, helicopters continue to be the go-to choice for many film-makers, news stations, search-and-rescue missions, and even military forces for certain types of operations. It’s even possible for the likes of you and I to take a spin in a helicopter. Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe, the Grand Canyon in Arizona, the Fox and Franz Josef Glaciers in New Zealand, Maui and Molokai in Hawaii - some of the most spectacular views of some of the most incredible sights in the world can only be seen by renting an hour or two in a helicopter, and by all accounts, every one of these trips is truly spectacular.

But today I want to talk about a different helicopter trip. One that no human has ever taken, but is perhaps more spectacular than any other in our lifetime. I’m talking about the first helicopter flight on a planet other than our own. I’m talking, of course, about the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter.

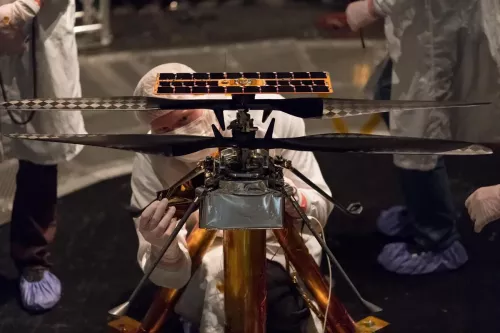

Ingenuity was built as a proof of concept piece. While so many of NASA’s rovers and deep space explorers are classified as Class B missions, using ruggedized hardware and software designed for the rigors of space, this Mars helicopter was classified as a technology demo. This allowed the team a little more flexibility and freedom. This meant that they weren’t relegated to specific, tested and verified parts for the build. This turned out to be supremely important.

One of the biggest issues facing the engineers was Mars’s lack of atmosphere. The Martian atmosphere is only about 1% the density of that on Earth. That means that lift would be very difficult to achieve and maintain, so the helicopter would need to be as light as possible. As an example, if you’ve ever gone up into the mountains to fly a drone or UAV, you’ve no doubt noticed that it has a bit more trouble getting up into the air. That’s because the atmosphere is thinner the higher we climb. A helicopter on Earth can reach a maximum altitude of about 25,000 feet (7620 meters) before the air is too thin to support the craft on its blades. The atmosphere on Mars, however, is the equivalent of trying to fly at 80,000 feet (24384 meters) on Earth. This meant that the craft had to be as light as possible. Theoretical calculations dictated that the craft would weigh no more than 4 lbs, or just under 2 kg. The standard computer used for operating most spacecrafts is the RAD750 from BAE System, which weighs about a pound. Using one fourth of the craft’s entire weight allowance wasn’t feasible, and without the constraints of a Class B mission, the team was free to look for alternatives. They wound up using a Qualcomm Snapdragon 801 processor, which was lighter, more powerful, and far less expensive than the RAD750.

Off-the-shelf parts became an important part of Ingenuity’s build. Rechargeable batteries, avionics, cameras and sensors could all be sourced from companies like SparkFun, and used not only for initial prototyping, but for the actual mission itself. In an interview with IEEE Spectrum before Ingenuity even had its feet on Martian soil, JPL engineer Tim Canham talked about the importance of being able to use commercially available parts from start to finish, and calls out SparkFun and the laser altimeter they used for takeoff and landing. (Good news - you can still get one for the next mission, regardless of how far from home it is!)

A TIMELINE OVERVIEW

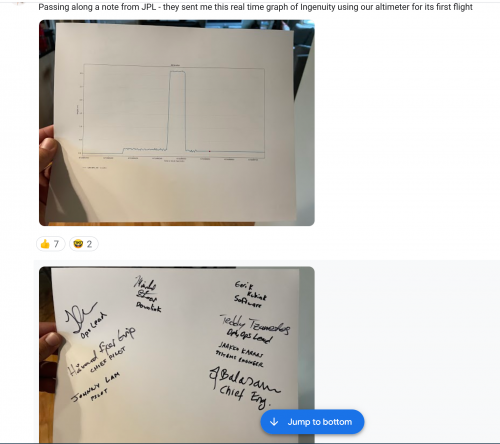

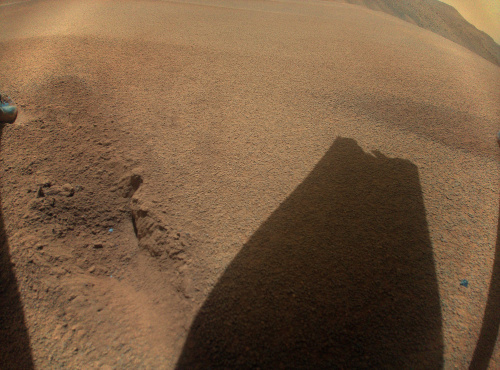

The Mars Perseverance placed Ingenuity gently down onto the surface of Mars on April 3, 2021. The first test was simply to see if Ingenuity would survive the night, and still be able to communicate in the morning. On April 4, success of the first step was confirmed. Four days later, the rotors were sent a spin test command, which it executed perfectly. Then, a week and a half later, on April 19th, 2021, the Mars Ingenuity Helicopter successfully completed its first flight, the first powered, controlled flight of any craft, on a planet other than Earth. It was an extremely exciting day, and while I don’t know if I can speak for SparkFun as a whole, I know that personally my primary interest was focused on seeing the helicopter execute a perfect landing. After all, I had been bragging about SparkFun parts on Mars, and how the Lidar Lite v3 would assist in the craft’s landing. I really didn’t want any issue to appear in any way to have been due to a part from SparkFun.

Thankfully, the lift-off, flight, and landing all went off without a hitch. By NASA’s own account, this meant that the entire mission of Ingenuity had been a success! They have proved that controlled, powered flight on Mars was possible. An amazing feat by a group of incredibly smart and cool engineers at NASA JPL. Oh, and if you’re wondering whether or not they are actually cool - after that first flight, the engineers sent Glenn, our CEO, a signed copy of the real-time altimeter reading from that first flight. Coolness confirmed!

Ingenuity started with the intent of making five total flights, with only the first three flights having been pre-planned, all of which would be completed within thirty days. The first three attempts would take off and land in the same spot, although for flight number three, they hoped to be able to get the helicopter to lift off, travel approximately 50 meters, then return back and land at its original spot. The first three flights were completed within a week, and for all of them, Ingenuity performed beautifully. For the next two flights, Ingenuity would do a little more traveling. On April 20th, the first attempt of flight 4 failed when the onboard software did not transition to flight mode. Heads were scratched, coffee was consumed, updates were sent, and by the next day, Ingenuity completed its fourth flight, this time traveling out 130 meters for a little scouting venture of what would be called Airfield B, taking both color and black-and-white pictures, then returning to settle back down at its starting point. In addition, the Perseverance rover recorded both video and audio of the flight, making this the first interplanetary vehicle to have its sound recorded outside of Earth. Then, on May 7th, 2021, Ingenuity made its final flight of the initial five, and touched down at its new point, Airfield B, some 130 meters from its origin at Airfield A.

The little helicopter still had power, and since the initial results and returns had been so good, they decided to continue forward. After all, any more information gained at this point was pure bonus. So on May 23rd, Ingenuity ventured past its original 5-flight mission, and completed flight 6. This flight lifted up to ten meters, and at 4 km, its fastest airspeed yet, and landed just over 202 meters away, at landing Airfield C. There were some in-flight issues, and the craft wound up turning off the navigation camera and flying solely on IMU. This was the first time that Ingenuity had to land at a site it had not previously surveyed, but had only been surveyed by MRO satellite. Harrowing as it was, the sixth flight was a success.

After that, the little copter that could just kept on going. It recorded its tenth flight on July 24th, traveling 240 meters to what would be its seventh landing site, Airfield G, and taking surveying images along the way. At this point, the helicopter changed to a surveying mission, to aid the work of the Perseverance rover. It would go out on scouting trips to help dictate the best travel path for the rover as it made its way around Jezero Crater. Some of its highlights include:

Flight 12: Longest duration. On August 16th, 2021, Ingenuity spent 169.5 seconds in flight, the longest of its missions.

Flight 25: Longest distance. On April 8th, 2022, almost a full Earth year after Ingenuity’s first flight on Mars, the vehicle flew for 708.91 meters to Airfield Q, its 17th landing area.

Flight 61: Highest altitude. On October 5th, 2023, in a test of Ingenuity’s flight envelope, the craft lifted itself to an altitude of 24 meters, for a flight that lasted over two minutes.

Flight 62: Fastest land speed. October 12th, 2023. “Hey, remember last week when we saw how high we could go?” “Yeah.” “Wanna see how fast we can go?” “Sure!” Ingenuity reaches a speed of 10 m/s, or 22mph, for a flight of just over two minutes. Flight 72: Final flight. On January 18, 2024, after a short flight for a systems check and verification, images from Ingenuity’s horizon and navigation cameras showed clear damage to the tips of its rotors. It was obvious that the craft would no longer be capable of stable flight, and at that point NASA had no alternative but to ground the helicopter. A week later, on January 25th, 2024, NASA administrator Bill Nelson announced that after three years on the red planet, Ingenuity’s mission had come to an end.

LOOKING AHEAD

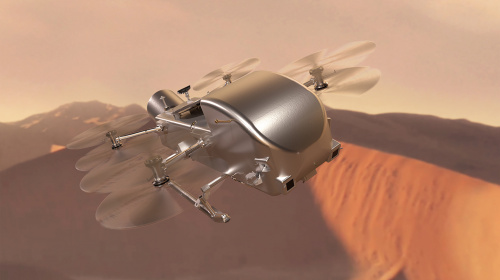

While future critical NASA missions, i.e. those involving human life, will continue to use space-rated hardware, the lessons learned from Ingenuity’s tremendous successes will no doubt allow for more freedom when designing technology demonstration missions in the future. According to NASA’s Theodore Tzanetos, Ingenuity Team Lead, “This is a massive victory for engineers.” Using off-the-shelf components will allow for tech demo missions to be less expensive, lighter, and higher-performing. I personally am very excited for NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission. I also know that when, at some point in the future, I see images being sent from a helicopter on Titan, or our moon, or any other celestial body, I will always think back to when NASA put parts from SparkFun on Mars for the very first powered flight from anywhere other than Earth.

WANT MORE INFORMATION?

If you, like me, can’t get enough info on things you find fascinating, here are a few links to keep you learning.