Whatever Happened to The Future?

What happened to our enthusiasm for "The Future," and how is the Maker Movement bringing it back?

If you haven't read William Gibson: Do it.

It's okay, I'll wait. Just pick up anything and start reading. The science fiction novelist who coined the term "cyberspace" continues to have a keen eye for the ways in which culture is driven by technological change. Recently I had the pleasure of reading a collection of his non-fiction works, published just last year, which illustrates this unique talent of his. Distrust That Particular Flavor is comprised of the various talks, book forwards, articles and essays that Gibson has published, however reluctantly, over the course of his career so far. One essay in particular (a speech, actually, given for Book Expo 2010) has left me thinking about The Future.

Not just the future as in our future, the time following the present, but "The Future" (with a capital "F," as Gibson puts it). The Future as in flying cars and moon colonies, where sky-scraping geodesic domes house cities of pure crystalline tomorrow. A leisure society where no one has to pull the levers of industry because the levers pull themselves. Where food comes in pill form. In a way, The Future was a promise made to us by science. I say "us," as in society, but I wasn't part of that "us," and I suspect neither were a certain number of you.

The "us" in question is my father's generation. Actually, he rode in on the last wave of a culture that might understand The Future (being born in '57). The War was over and America was hopeful that things were on the upswing, this before the Cold War nightmare had really settled in, and people were looking forward to the miracles of science that awaited them in the coming years. I've only experienced this second-hand - a general enthusiasm for the world of tomorrow passed on to me by my dad. He grew up reading (along with some classic science fiction) Popular Mechanics, a magazine that I still read today, and which has been publishing since 1902. I like to think of Popular Mechanics as filling the niche that Make Magazine currently fills but before the "Maker Movement."

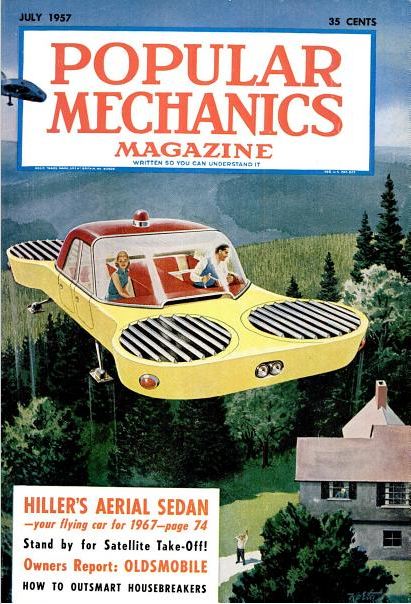

Looking at the Popular Mechanics back catalog, I can see that my dad could've opened a 1979 issue (he'd be around my age) and read all about "The airplane that will explore Mars!" He may have seen U.S. Air Force ads beckoning him to "Be a pioneer in THE AGE OF SPACE!" My grandfather may have even had a 1957 issue around the house which advertised "Hiller's Aerial Sedan: Your Flying Car for 1967!" These fantastic sounding articles were printed side by side with more practical DIY advice about passive solar heat, how to install a roll bar in your car or how to make a child's go-kart. That's because they weren't "fantastic," they were just... spectacular.

None of this is to say that there wasn't a healthy skepticism surrounding these ideas, but there was also a certain popular futurism. People were genuinely pretty convinced that the scientists and engineers that had gotten them through the war and into space were going to continue to propel them into "tomorrow land," (or at the very least make their cars hover a little.) Similar stories printed now, Gibson points out, typically elicit a lukewarm response: "Oh sure," or "Huh, no kidding." The wonder isn't gone, it's just not part of the popular culture anymore. Gibson calls this "future fatigue," the antithesis of future shock. Technology has been advancing at a rate that's so amazing that we simply expect the impossible. Also, the amount of pure "stuff" that we're generating along the way has caused us to develop filters for innovation, a hardy cynicism that's eroding away at the wonders of "The Future." Not to mention recent history hasn't been kind to the notion that science and technology will ultimately make the world a better place: The A-bomb, biological and chemical weapons, climate change... we're really wreaking havoc with the tools we've developed.

There was another aspect to The Future, though. It wasn't only the belief that science and engineering would naturally better us as a society, but also the ability to imagine a specific world made better. The Future wasn't some nebulous concept of betterment, it was an actual place and it came through in full-on raygun technicolor, whiz-bang contraptions in tow. By some form of cultural telepathy I think we all know what each other is thinking about when we talk about The Future, as if it were a theme park or a distant country. Gibson talks about my generation, and the next even more so, experiencing an "endless now," where the future is basically now but with more stuff. I think it's easy to believe that progress will just happen, and that "the rest of us" don't have to worry about it; but I would argue that the popular notion of The Future, that sparkling tomorrow-land, was responsible for a large part of the technological advancements we saw in the last part of the 20th century. We had a goal and we were, all of us, working toward it (consciously or otherwise). When I try to imagine what "The Future" means now, I still see the bubble-domed flying cars of my father's generation. I don't know what today's "Future" is. There are glimpses in our speculative fiction of future worlds generally wrought with either oppressive surveillance or apocalyptic waste. When I say "I want to build a better world," I don't have a mental image to attach to the notion.

Assuming we need "The Future," how do we get it back? What can we do to instill that same wonder in the growing population of makers? Maybe we can pick up where we left off. We have a design language for The Future, albeit an outdated one, and it still captures the imagination. Maybe by revisiting the retro-future aesthetic, we can reignite that spark that we need to build our own ideal world. Can we really go back to the future, as it were?

This is a series of cardboard toys that I designed to play with that idea. Classic retro sci-fi shapes that come flat-packed. You can bring them to life with lithium coin cells and LEDs (both of which are decidedly more modern tech.) The response from people who notice them sitting on my desk has been really cool to see. Cardboard robot-men, rocketships and laser blasters (especially laser blasters) seem to ignite some part of the imagination in people that isn't accessible to, say, an Arduino. Certainly the Arduino is a lot more futuristic (in a literal sense) than the cardboard rocketship, but the rocketship is The Future. Hopefully toys like these can open a dialogue across the generational gap about what it was like to dream of The Future, and spawn the next group of futurists who will dream up their own "rocketships" or "robot men" (which could just as easily turn out to be Mars colonies and genetic engineering or hopefully something we can't even imagine right now). Come on, give us something to aspire to!

I know the Maker movement is already full of people who are working on disparate but equally amazing versions of The Future. I wouldn't want to downplay the missions of groups like Not Impossible Labs who are using that energy to really make positive change in the world; practical solutions to immediate problems are always an admirable goal, and it does us all a lot of good for people to think that way. However, we need some truly fantastic dreamers, as well, and a common language for talking about the future. It makes me hopeful to see events like Bay Area Maker Faire, which I was able to attend with some other SparkFunions recently, because it showcases the really bizarre and fantastic right beside the immediate and practical. There's a lot of potential in that mixing of ideas and I think that the community it represents (that's you guys/gals) is doing a lot to develop a modern idea of The Future. I think the Maker Faire is probably my generation's equivalent to the World's Fair, but more inclusive and more participative, which reflects the values of our generation... I think.

At any rate, I suppose I don't know whether my generation (or modern society as a whole) really needs The Future, and I certainly wouldn't pretend to speak for anyone else. A large part of what drives my work with SparkFun, though, is the hope that our customers will be the city planners of New Future, as I've taken to calling it. And looking at my watch, we're probably about due for a paradigm shift.

Let us know in the comments what you think about The Future: Do we need it? Do you remember it from "back then," and is it an overrated product of nostalgia? And also let me know if I'm talking out of my rear; I'm not usually prone to this level of seriousness and I'd love to find out that I'm just late for the train to New Future.

A quick addendum to today's post: You've been waiting patiently (where does the time go??), and the time is belatedly upon us: CAPTION CONTEST WINNER. You guys. Great showing this time; we get the feeling a lot of you have been waiting for the perfect combination that is embedded electronics and prehistoric fauna. But there can only be one winner, and that winner is Member #430268!

Congrats, member with string of numbers! $100 in SparkFun credit is coming your way!