Google Ara Modular Smart Phone Developers Convention

The Ara Modular Smartphone Developers Conference was on April 15-16. We were there. This is what we learned.

On April 15th and 16th, Google held its first Ara Modular Smart Phone developer conference at the Computer History Museum in Mountainview, California. Ara is a project that is being spearheaded by Google ATAP, their "Advanced Technology and Projects" group, which is a stay-over from Motorola that Google kept after the Motorola sale. The Ara Project is their concept for a modular cell phone. They were forced to push the announcement of the project forward with the sudden popularity of PhoneBloks, a modular phone concept conceived by Dave Hakkens that went viral recently. The ATAP team had been working on the Ara modular phone for a while at that point, and decided to announce the phone as an answer to the popularity of the PhoneBloks idea.

Since the project's announcement, the reception has been mixed. The reactions seem to fall into two camps: the "I want that gimme that right now" camp, and the "That will never work don't even try and here's why" camp. That reaction notwithstanding, the DevCon this weekend was full of about 400 people who had formed an "Okay, let's see if we can make this work" camp.

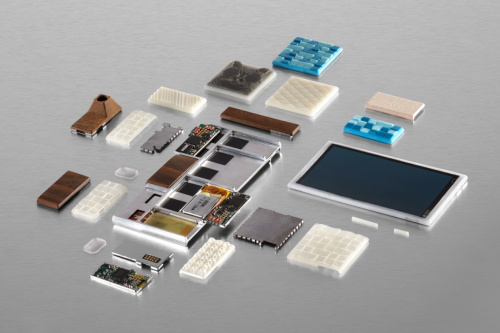

Google's message for the developers at the convention was clear; they need manufacturers and the developers-that-be to start building modules. They want to reach what they call a "demonstration at convincing scale," i.e. have enough developers and companies on board and time-invested by 2015 that the project has enough outside investment to demonstrate value. They've released a v0.10 Development Kit complete with reference designs, a high-level description of the platform, and an industrial design language to insure that developers build modules to their form-factor specifications. The conference highlighted all of the major systems and components of the phone, and gave developers a good starting point for module design. What follows is what I took from the conference, from the hacker/maker perspective.

Ara Base Platform (The Endoskeleton)

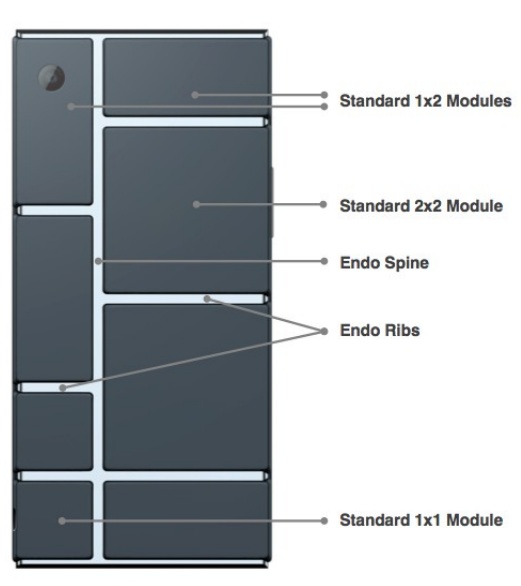

The base platform, or "Endo" as the developers refer to it. is what Google plans to manufacture and sell. They have a vision of users purchasing a bare-bones endo from stores that includes only the screen and wifi module. That's it. All the other modules will be purchased from their module store or other retailers. This way they can sell platforms, and not phone plans. Users will be responsible for purchasing a separate module from a cellular provider if cellular service is desired. This may be a frustrating step for consumers looking for a new phone, but for electronics geeks it's great news; Ara will be an off-the-shelf expandable hardware platform with a touch screen and wifi module that runs Android out-of-the-box. To me that's more exciting than the Ara's viability as a mass-market cell phone.

The Endo will house all the electronics that run Android and connect to the modules. The central controller will be the Texas Instruments OMAP4460, the chip on the PandaBoard. The central controller will connect to the modules via the MIPI Unipro network protocol. The MIPI protocol was developed by a consortium of cell phone developers to create a fast, universal protocol for connecting peripheral hardware in cellular designs. Modules will connect to this protocol using a special chip that the Android will recognize. The chips require a special driver in Android, that is currently being compiled into the kernel.

Right now, the only method the Ara group has offered to connect a user-designed module to the backbone is an FPGA with an instantiation that talks to MIPI. This FPGA then tunnels protocols like I2C and GPIO to the module. The problem with this FPGA solution is that it is expensive, high-power, and large. For the future development, Toshiba has promised to manufacture a specific ASIC that will solve these problems and connect the module to MIPI natively. Google will provide a driver that will automatically recognize this ASIC, making module hardware development much more streamlined.

Electro-Permanent Magnets: How Do They Work?

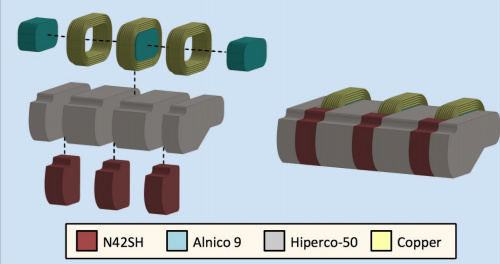

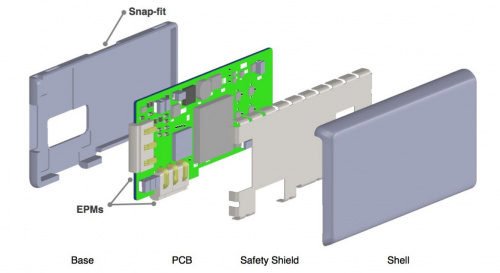

Another interesting feature of the Ara phone is the way the modules are held in the Endo. Mechanically, the modules slide into the slots on the back of the phone and are held in the x-direction by dovetails. In the y-direction, however, they are held by electro-permanent magnets, or EPMs. Magnets that can be magnetized or demagnetized with a burst of electrical current. They draw no power unless they are changing state. The idea is that the user inserts the module, and the EPMs automatically magnetize to hold the unit in place.

Before the conference, I couldn't find these magnets for sale anywhere. I cornered one of the Ara team members at the conference and asked where I might purchase hundreds of these, and I was told "No one is actually building them yet. The EPMs we have we had to build by hand." Frustrating.

Industrial Design Language

Google spent a good deal of time at the conference discussing the Ara's industrial design. They've developed a very specific set of rules for module developers. The modules can only be so big, so hot, and so high-power. The also talked at length for their plans for manufacturing the coverings for the Endo. Stated simply, they plan to 3D print everything. Consumers will be directed to a site where they can design a fully custom enclosure for their phone that will be 3D printed on a special printer that is being designed by 3D Systems. It's certainly exciting to see a company planning to manufacture a mass-produced product on technology as young (and open) as 3D printers. Be sure to check out the MDK for a full run-down of their industrial design language.

Module Design Tools (Metamorphosis Software)

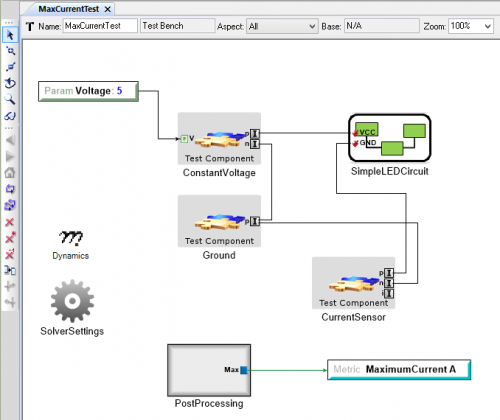

Along with hardware guidelines for developers, Google has contracted MetaMorph Software to build an interesting design tool for module developers. The tool is called CyPhyML. It is built upon the open-source CyPhy software developed by DARPA for rapid prototyping and virtual environment testing.

CyPhyML is not a CAD program, but rather an "umbrella" program that integrates several CAD programs and facilitates the design process by translating a CAD model designed in one program (like a layout in Eagle) to a model in another program (like a 3D model in Creo). CyPhyML takes the design from the part-level to the module level, and facilitates tests like Spice models and heat dissipation. The designers tried to keep the "utility programs" as open and available as possible. The tool is a bit too comprehensive to describe here, but check out metamorphsoftware.com for a basic run-down. The software has yet to be released, but the tool has a lot of potential for wide use in the prototyper market.

Licensing and Distribution (Play Store for Hardware)

To sell the modules and make them available and understandable, Google has plans for a "Play Store for Hardware." In other words, the modules that they approve will be sold through a special repository, like the Play Store for applications, where users can search through tested-and-proven hardware modules to build a custom phone. There was not a lot of talk about the fees and processes associated with this "approval process", but there wasn't anything to suggest that a developer couldn't develop and sell a "non-approved" module without going through an official Google approval process. How Google is going to deal with these renegade modules remains to be seen, but the promised availability of the Toshiba ASIC and openness of the CyPhyML software is a good sign.

What this means for DIY'ers

As I stated before, the most exciting part of the Ara project is that Google plans to mass-produce cheap Android platforms that include a touch screen and wifi module in stores. That in itself should get a geek's blood flowing. As far as hackability, there is nothing to suggest that the Ara won't be super-hackable. The ASIC that Toshiba has promised and the EPMs (that no one has promised, yet) seem to be the only pieces of specialized hardware that designers will require to build modules. The seeming "openness" of the CyPhyML software is promising, and may turn out to be a useful tool for hobbyists even if the Ara platform doesn't succeed as a mass-market cell phone. To keep an eye on the project, bookmark the Ara Developers Google Group for the latest.