Enginursday: KiCad and Open-Source Design

The process of using open-source designs to get to a final product, featuring KiCad, PJRC, and Advanced Circuits.

Buckle up kids, it's Enginursday! This week I bring you the process of using open-source designs to get to a final product, featuring KiCad, PJRC and Advanced Circuits.

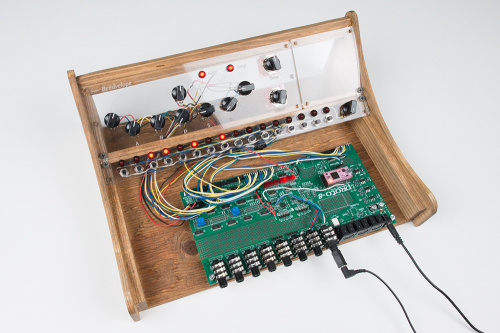

As a hardware engineer, a program is a thing that lives in a black box and it's up to me to get it out. Looking at a standard 328p type development board, this means adding knobs, buttons, displays, and periphery that control or can be controlled by the program. So, solder on some wires and breakout boards, zip tie the whole thing together and you've got yourself a bonafide prototype.

But my prototype doesn't have any knobs on it! As a prototype, it uses the midi bus to get knob data from a midi controller, allowing me to test my code. It's a convoluted process that involves double checking IN/OUT cables, using counter-intuitive midi controller programming/bank selection, and a nasty spreadsheet that maps controller numbers to parameters so I can keep them all straight.

What I'd like to do is just wire knobs to it. Unfortunately, micro-controllers only have so many pins, and I want more. Lots more. Hundreds. And I don't want to solder all these goofy wires and muxes together. It's time for a prototype PCB.

Create the Spec

Specifying was an interesting lesson in college. The only time it was really talked about was during senior design, 4th year. The students prefer a hard-and-fast set of rules that they can blindly follow, but the process of figuring out a product's final form can be highly organic.

For this project, I discussed thoughts with fellow engineers. Scribbled on white boards. Wrote lists, then threw them away. I asked, "How big is it? How many features are there, and what are they? What voltages will it operate from?" Eventually I came to a list of things that would always be present, and I knew I had a place to start.

Find Some Reference Designs

At this point I'm about 80% sure what the product will be, but focusing in will have diminishing returns so it's time to get what I know down on paper.

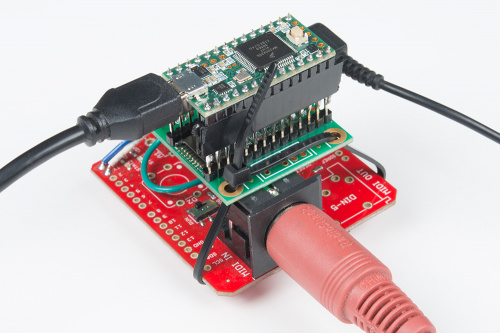

This is where the open source comes in. I know I want it to have MIDI ports, teensy audio, and some button matrixing, and the thing will need some power. I collect the following references:

Armed with these, I can approach the design.

Get the Components Ready

This is a little bit of a leap. I haven't done any design yet, but from experience I know the next "productive" step is to enter the schematic into the EDA (electronic design automation) tool, flip to layout and start drawing. BAM! There it is. In order to use a component in a schematic, I need to have a symbol, which I may need to generate myself. I don't want to be making a new symbol every time I need one, I want to start my schematic and do it all. The solution: Get all the components ready first. For your own sanity.

There are a few things to do to make new parts. Get the datasheet for each part not currently in the library. If possible, I like to have the physical component on hand as well. Often I notice something not drawn in the mechanical section. The datasheet also serves as a guide on how to make the symbol. When in doubt, draw it like the manufacturer drew it. It's convenient to also make the footprint at this time, and having the component in my hand allows me to move it around with other components and think about what a reasonable distance between components would be, and to double check mirroring of the layout. If I can see the part, I know if I'm looking from the top or bottom.

KiCad's component system is a little different from the Eagle system I come from. In KiCad, the component symbols and footprints are kept in separate files. Between the schematic entry and layout phases, footprints are associated to components in the schematics (using the CvPcb tool).

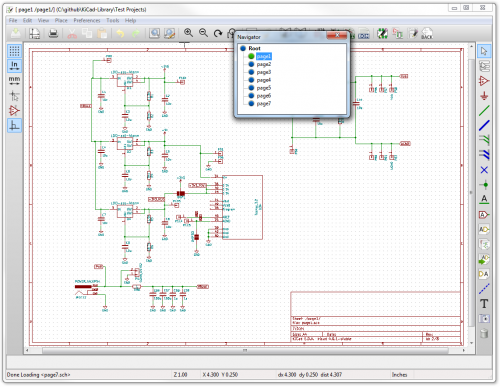

Enter the Schematic Design

With references and components in hand I can start the schematic. I go back and forth between researching stuff and entering diagrams. I've found that even if I think I've covered 100 percent of the design, I realize what I forgot as soon as I try to enter the schematic. Often the realization comes as a, “Wait a minute, what's this pin for?” thought, or, “Wow, I drew this symbol way out of scale!”

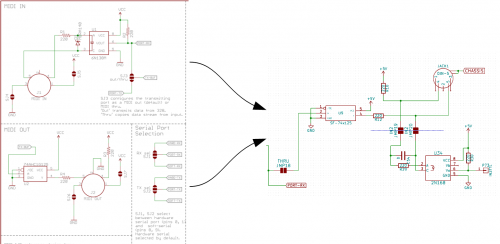

The general idea is to convert all reference designs into schematics for the tool. First, enter the core of the reference design -- that is, things that connect only to other things in the original design. Then, connect the cores together. For me, I entered the following cores:

- The midi shield core

- The Teensy schematic diagram

- The power supply (LDO) stuff

- The codec as in the Teensy Audio board

Using the reference designs allows me to trace connections through the original product's ports in order to get them wired up correctly. I could stare at tables in datasheets until I'm blue in the face, but I'd still have a chance of swapping TX and RX. With the reference designs, I get to see what worked for someone else.

When all the reference designs are in there, kind of as-is, it's time to connect the various designs as stacking the shields would have done. Remember the zip-tied stack of proto earlier? I need to make those connections. Again, I start with what I know, and create lists of the things I hadn't thought about while doing what I know.

An example that came up while working with the LDO (Low-dropout regulator) sources was the option for using the Teensy's output regulator to source the 3.3v rail. I was planning on using an LDO for this rail and hadn't thought about the Teensy's regulator until I saw the pin in the schematic. This lead me to use a three-position jumper to allow sourcing from either. This came in handy when my 10-year-old prototyping resistor on the LDO's feedback started to drift, and I was able to swap over to the Teensy. It's little decisions like this that can lead to a good product, but can also lead to scope creep and over-engineering.

The best part about open source is that a design can be modified if it doesn't suit a need. I wanted a third MIDI port to use as a thru, but maybe for some other purpose. I combined the IN and OUT parts of the shield design onto a single jack so that either function could be selected.

Start the Layout

Having received enough abuse from the schematic entry tool, I needed to see what it would look like on the board. Eagle is nice because it handles synchronization between schematic and layout automatically. KiCad does not, which can be good and bad. The bad side is that I have to figure out how to do it myself, but the good side is I have more control over the libraries and associations. Do you want to associate that 1x8 0.1" header to an 8-pin IC symbol? Sure! Go right ahead!

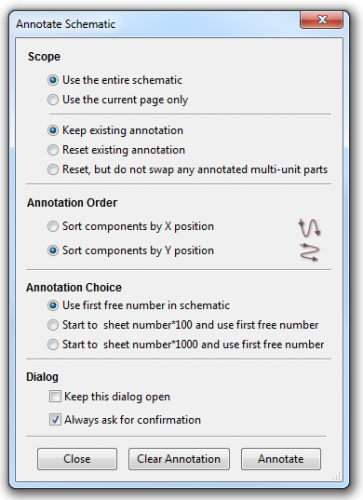

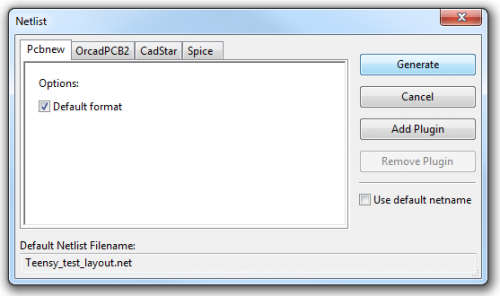

Where Eagle uses a single button to switch to schematic, KiCad makes you do a dance. First, I annotate the schematics. This goes through and applies names to all my unassigned components. It works page by page in horizontal or vertical scanning fasion, applying names like JACK9 and U14, etc. The next step is to associate footprints to the symbols in the schematic. Having done that, a netlist is generated and saved. This netlist is what the layout editor uses to decide what exists and how it is connected.

Use "Annotate Schematic" to apply reference designators |

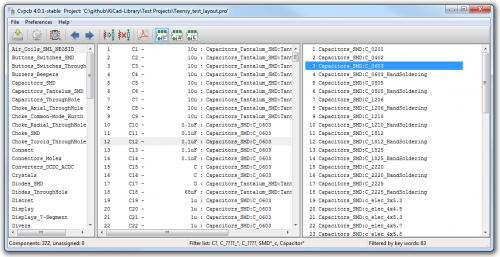

Pick a footprint for each component using Cvpcb Pick a footprint for each component using Cvpcb |

Generate a Netlist for the layout editor (Pcbnew) to use Generate a Netlist for the layout editor (Pcbnew) to use |

All the work up to this point was really to answer one question: “Do the layout ability and interactive trace dragging features of KiCad work, and are they useful?” I know, that's a lot of legwork just to play around with an open-source interactive router... what am I saying? I've been wanting for this for years! Let's get in it.

Iterate!

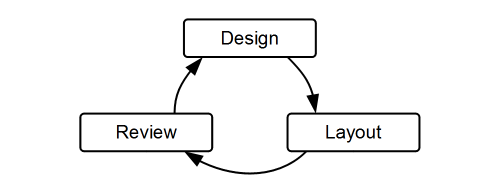

It wouldn't be Enginursday without a diagram that oversimplifies the engineering process! This time it's to show that the layout didn't just happen. Something was tried, and the validity of that idea was considered, and a new thing was tried.

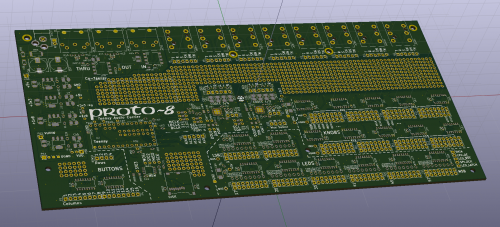

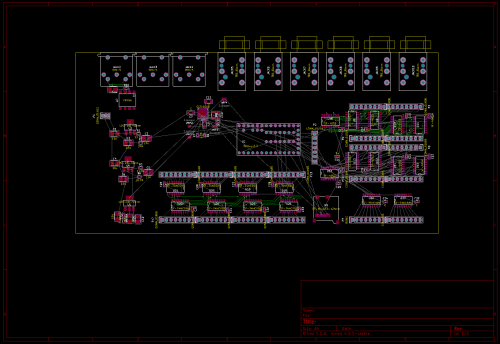

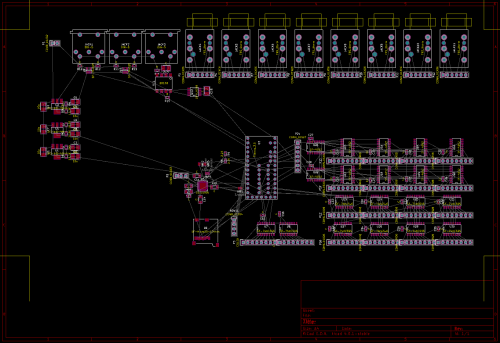

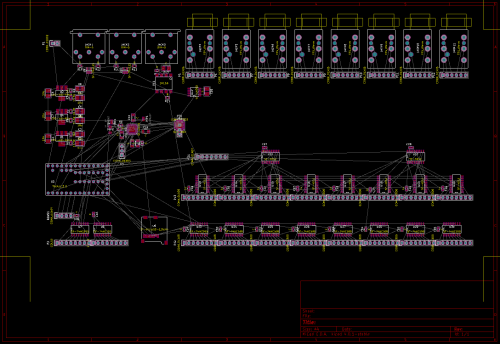

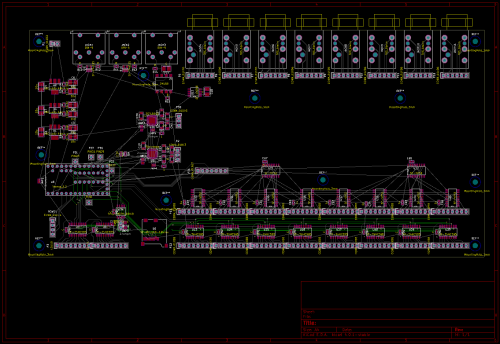

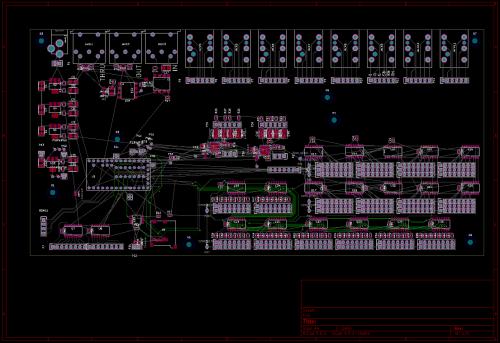

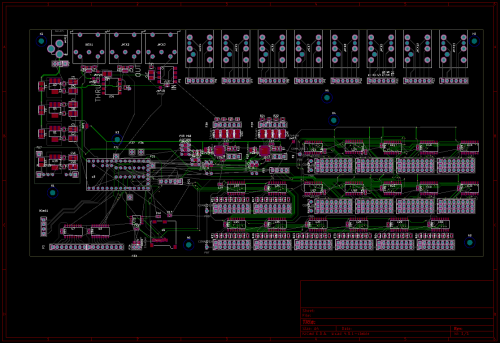

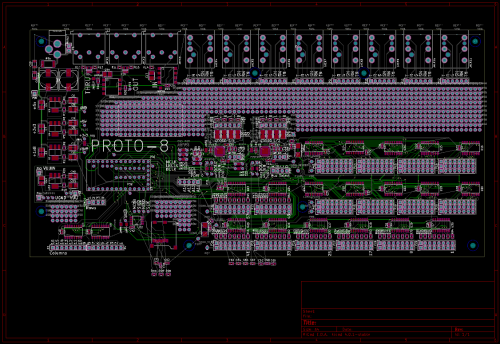

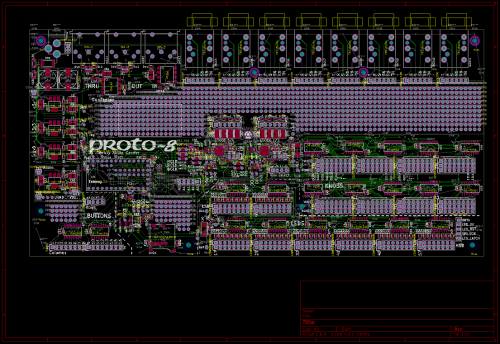

For this design, I started with a smaller board and experimented with various orientation sections before coming to the final solution. Sometimes I tried doing a little routing here and there to see if I was on the right track. In the following pictures, I show snapshots of this progress. I think it's interesting that the difference between the early designs is huge, while later in the process the changes are more of a refinement, and not much major movement occurs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

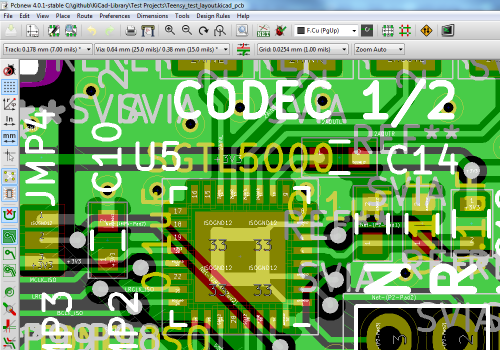

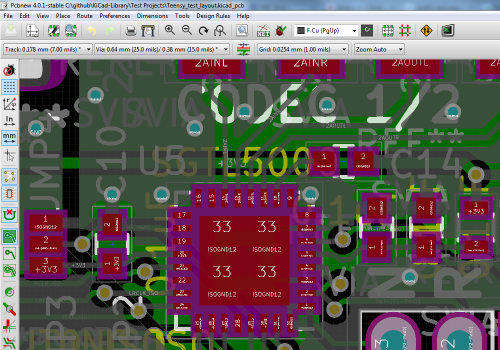

KiCad and Layout

To me, the thing that makes KiCad stand out as an EDA tool is the ability to do interactive routing. Having worked in a button-up engineering firm, I always saw the PCB department dragging traces around. It looked a lot better than the 'ol rip-up and re-route method I was used to.

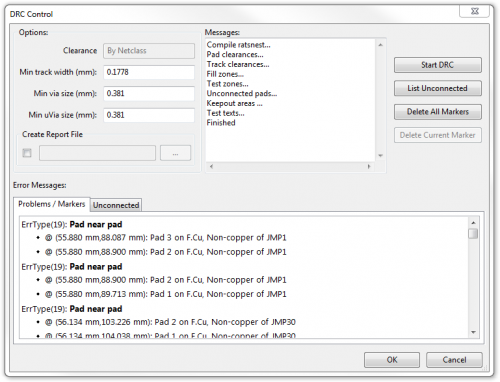

To get KiCad to do this, it needs to know something about the signals and how close together they can be. The clearance of traces (and default widths) are set within the Design Rules Editor, a function of Pcbnew. I found that it was easy to set up various rules, and that they are mappable to any of my signals. I ended up with four signal classes (Jack Interface, JackLine, Power, and Signal, plus default) and was able to get all the spacings I desired.

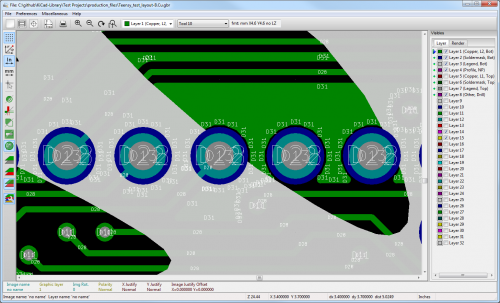

Calculating and displaying moving traces is also quite a task. KiCad handles this by using OpenGL, which is turned on in the layout editor. Some tasks work in OpenGL mode, like interactive routing, while others didn't work so well. I found the OpenGL mode had troubles setting an origin right on grid. It wanted to snap to other places that didn't make any sense. But, the native display mode had great snap to grid. The open-source solution is to switch between the modes with the function keys.

Viewing the layout using native graphics (F9 view) |

Viewing the layout using OpenGL graphics (F11 view) Viewing the layout using OpenGL graphics (F11 view) |

I found a lot of features of KiCad seem to work best with hotkeys over navigating menus. Once I learned them, their usefulness was apparent, like B and CTRL-B to fill and un-fill polygons, and the mouse-centering feature. I view a lot of open-source software as something unrefined where I need to learn how the programmer liked to use it in order to get the most from it. Fighting with an open-source tool because it doesn't work how I'd like usually ends in frustration.

Finish and Prepare for Fabrication

When I'm finally happy with where the parts will be, it's time to start tweaking. I chose to use reference designators on the silk, which means they need to all be the same size and placed in useful locations.

Once the designators are done, I took a moment to show some pride and dress it up in silk. The KiCad bmp-to-shape tool is as buggy as everyone else's, but I had success. I found the best method was to get something meaningful to come out of the tool, measure how big it is, how big I want it to be, then re-process with a different scaling factor.

Another oddity I found was that the tool would only produce silk layers. It's open source though, it's open for me to look at! I found that the footprints are saved as text, and noticed that I could change the layer tag to move the layer.

Another tool I found useful was the board render feature.

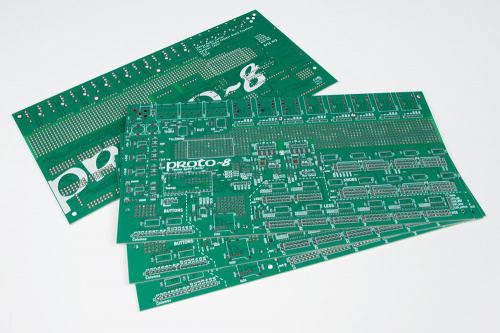

With the board looking good, it was time to check if the board meets the PCB manufacturer's rules. I ordered boards through Advanced Circuits $33 each proto service, which lists the minimums clearly on the landing page. This service comes without an electrical test, so it's possible I made shapes that can't be fab'd and no one noticed. The interactive router used design rules so it forced clearance, but running the DRC popped up a bunch of hidden copper and unconnected traces that looked connected. It's good to use the rules and run the DRC.

The last step was to produce gerbers for the manufacturer, which KiCad handled like a champ. It also has a nice feature for viewing gerbers, which turned out to be more beneficial than I imagined. Many PCB services offer a gerber viewer, and the demos look great, but I couldn't get it to function on my home computer. KiCad's viewer was the last time I saw the design before getting a package of PCBs in the mail.

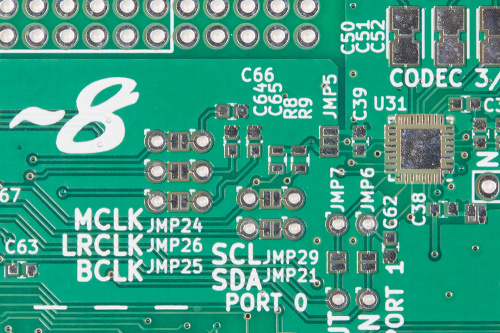

After an anxious week the package arrived!

|

|

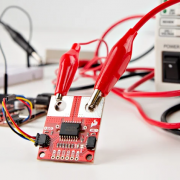

Bring Up the Prototype

Bringing up a board is probably a post on its own, but I have to say something about it. I didn't just load all the components up and apply power. That would be a sure way to get the smoke out. I assembled it in stages, testing between stages. First is the regulators, then the Teensy. Next, the QFN was reflowed and the audio systems tested. Lastly, the IO logic was applied.

Finally, I have access to the black box.

You Can Do It!

I started this project simply because I wanted to try the interactive router. After pushing some traces around I decided to expand the test and try a new PCB service, and the whole project exploded into what it is here.

My basic approach to learning was to watch long, dry tutorials on YouTube. I found a good method was to put them on my second monitor and let them play as I was doing tasks such as building components, researching designs and checking references. Ya know, engineer-y stuff. This gave me a cursory knowledge of what was in the long tutorials. Later, when I needed to do a new task (like working with polygons), I could recall where that information was covered and re-watch the part of the video that was relevant.

Here's some of the videos I found useful:

- KiCad Interactive Router (release version)

- Introduction and KiCad Project Creation

- Creating Power and Ground Planes In KiCad

- KiCad Tutorial #6: Create PCB footprint component

Basically, Anything by Chris of Contextual Electronics, or Tom W, is loaded with good information.

Good luck, and have fun!