Automated Conference Room Signage

Using a Raspberry Pi and the Google Calendar API to avoid Meeting Room Mayhem.

Among the various growing pains that SparkFun has experienced over the years, perhaps the most persistent has been the proliferation of meeting rooms leading to a variety of mid-meeting interruptions and snafus. Don't get me wrong; it can be nice to break up a long meeting with the occasional, "Oh sh-t, this isn't my meeting, is it?" or "Are you all gonna be in here much longer?" But there comes a point when real work must get done. Google's so-called "G Suite" has solved many of our problems in this department. Each conference room is a "resource" in the Google Calendar, which can be reserved and scheduled so we're not double-booking our meetings anymore. However, we have quite a few meeting rooms in the building, and it can be easy to forget (or assume) where your meeting is scheduled until you find you've just been introduced to a vendor who is not in the meeting you thought you were in.

Generally speaking, meeting organizers are very good at using Google Calendar to schedule their events. The breakdown occurs in meatspace when attendants are faced with two adjacent meeting rooms and no memory of which starship-themed name was on the calendar invite. Sure, they could check their phones, but when you're late for a meeting and your chances are 50/50, you're barging in! This is a minor inconvenience when it happens once...but after it happens a few times, people start grumbling. I personally don't mind a little derailment every now and again during meetings. What I do mind, however, is grumbling. So I set off to find a solution...to the grumbling, mostly.

A Signage Solution

My best idea (short of forcing everyone to add every meeting room to their calendars) was to create some sort of automated signage for every conference room. Now, there are plenty of pre-existing solutions for conference room and convention center signage, but most of them seem to depend on running a sign server somewhere to control them all. While that's not a big deal at all, it's also not necessary because we already have a server that's holding all of our event information for us, and we don't have to administer it! Ideally, each sign could query Google Calendar independently so that adding more signs to the system would be as easy as just adding a new resource to the calendar --- no server need ever be aware of the sign's existence.

So obviously I'm going to need some kind of small, network-capable compu—rrrrrraspberry pi. I mean, let's cut to the chase --- it's gonna be a Raspberry Pi; everything is a Raspberry Pi now. In this case, though, I'm not just bandwagoning. The Raspberry Pi is a particularly appealing platform for this project because of the well-supported 7" touchscreen display that's available for it. The Pi and the screen together make a really tidy stack that will do everything I need from a small digital sign.

Designing an Application

From the outset, I knew I was going to write the application in Electron. If you're not familiar with Electron, it's a cross-platform development framework that allows you to basically write web apps with access to back-end modules through NodeJS, or, if it's easier to think the other way: It allows you to write GUIs for NodeJS applications using HTML and CSS. It basically connects Node to a dedicated browser window running the Chrome V8 JavaScript engine. Electron is very similar to NWJS, which I wrote about in an earlier blog post. In fact, I should thank user David C. Dean for mentioning Electron in the comments section. That eventually led to me using it in developing the GeoFence application.

In the time since David introduced me to Electron, someone had solved the problem of missing ARM Linux binaries. In fact, someone else had already wanted to use Electron for their digital signage, and they wanted it badly enough that they rolled a Linux distro around it: BenjaOS. Benja is an Arch Linux distribution targeting single-board computers that's pre-configured to launch an Electron app on boot. This is a job it does very well, once you've figured out the quirks in their flavor of Electron application.

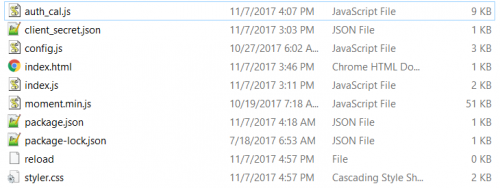

I won't go over the process of developing the application logic and GUI, but I will take you through the final code because it's really not that verbose! In the app directory, there are quite a few files, but that's really just for modularity, and there's not a lot of code between them. When Benja boots, it runs an index.js file, which in turn launches our browser window and loads up the index.html file. The html file, of course, contains the markup that describes the layout of the GUI. It also pulls in the stylesheet, a few libraries and finally the config.js and auth-cal.js files.

Most of the work takes place in the auth-cal.js script. The largest chunk of the script has to do with authenticating ourselves to Google. In order to access the resources for SparkFun's Google Calendar, the application needs to authenticate as a user who belongs to the SparkFun group. I filed a bug with IT to set up an account specifically for the signs, and they were happy to oblige! I used this account to generate Calendar API credentials through the Google API Console. The auth-cal script uses these credentials to request API access, which gets me part way to where I want to be. Then it uses the API access to ask for user authentication, which gets me access to the SparkFun calendars. The first time this script runs on a new computer, it requires me to log in on behalf of the signage account for authentication, but it stores the access token after that.

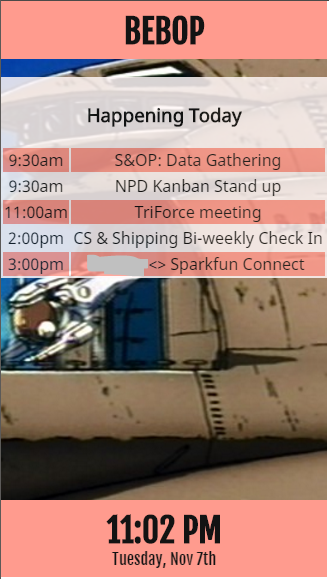

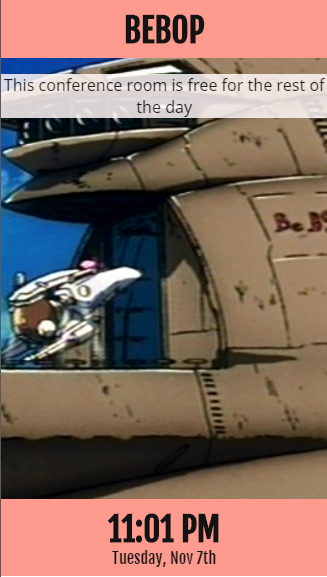

Once the authentication is done, the auth-cal script handles the sign logic. It makes Calendar API requests to constantly update the agenda and display it on screen. It also takes advantage of the (beautiful) momentjs library to keep time and calculate the time between events. Finally, it pokes the DOM to flip back and forth between two different UIs: One with the whole day's agenda and one that gives you the current event (or time until the next event).

The stylesheet is written to present the GUI in portrait orientation, since the main function of the UI is to present long lists. Instead of trying to rotate the framebuffer in Arch Linux, I decided to use the "-webkit-transform" function to rotate the entire page object in the browser. This worked out fine once I compensated for the weird position offset that it produced.

If you want to dig into the code for yourself, you can check it out at the GitHub repo.

...And Benja was his Name-o...

Installing BenjaOS and getting my application to run was a little confusing because the documentation is pretty sparse. Luckily, the example application is fairly well-commented, so it was easy enough to learn by example. First, the installation is as simple as downloading the appropriate disk image from Benja.io and writing it to an SD card. Throw the SD card into your Pi, and you're ready to boot up! The default application shows the device's IP address, which makes it easy to SSH into the device (user/pass: benja/benja) as well transfer files over SCP. Notepad++ also has a pretty handy plug-in (NppFTP) for working on projects over a network connection. If you're not into SSH, you can always pop that SD card back into your computer, and the app folder will be represented as its own drive ("BENJA APP"), which you can edit locally.

The thing that I burned a lot of time figuring out is that you don't want to just drop your standard Electron app into that folder. Benja has a special package.json and index.js file that differ in their approach from the package.json and main.js file you might find in other Electron apps. You'll want to keep those instead of trying to use your main.js file. The rest of your project should work as usual, however if you have any node dependencies, you may need to install them with npm. Simply SSH into the RPi and run npm install -g

It Works!

In the end, I'm pretty happy with how this project worked out, but I guess time will tell how well it solves our meeting-time troubles. I'll keep you updated because I'm still waiting on enclosures and wire covers to install these signs by their respective rooms.

I know some folks are intimidated or bored by application programming, especially in web language, but it's time makers embrace these languages and skills because IoT appears to be coming, whether we like it or not. Add to that the fact that every few weeks seems to bring fresh new Linux SBC, and it's likely that we're all going to be doing a lot more programming in the "web back-end" realm, either via Node or Python or...well, you get the idea. So what do you think? Give web a chance?

Happy Hacking!