15 Years of SparkFun

To celebrate our "crystal anniversary," here's a collection of the stories, blog posts, products and adventures from 15 years of making crazy things.

It’s been 15 years since SparkFun started building crazy stuff. Let’s take a long moment and look back to see how it started. Perhaps from history we can see where we might be headed. I enjoy telling a good story, and you’ve got me wading through memory lane. Grab a tasty beverage and have a read...

The years:

- The Origin Story

- 2003

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- And Beyond

Origins

In 2002 I was getting a degree in electrical engineering, but all of my classes were pure theory. I could create a Bode plot and calculate a required RC combination for a notch filter, but actually build something? That was outside the bounds of all my classes.

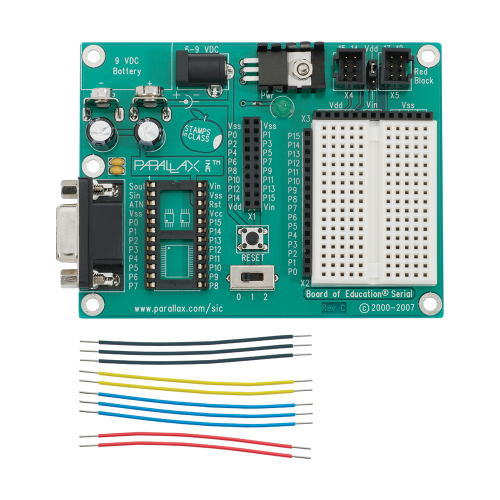

My problem was that I wanted to build a device that could read a few sensors and amplify voice. It was a device for the sport of rowing. To accomplish this I started to root around in the world of microcontrollers. My first stop: the Parallax Board of Education:

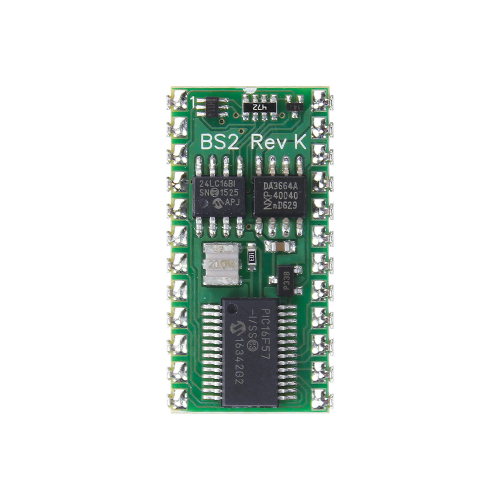

A brief lesson in the history of the microcontroller: Original microcontrollers were one-time-programmable (OTP). This meant you loaded code onto the device once, and that was it. If you’re like me and often screw up code, OTP meant you would end up spending a fortune on microcontrollers as you tested your code again and again. The folks at Parallax figured out how to combine OTP microcontrollers with flash-based EEPROM, and the BASIC Stamp was born. The Stamp had an OTP microcontroller (a PIC 16 series) that had an interpreter burned onto it. The user would write code in BASIC, the code would be compiled into pseudocode and then uploaded to the EEPROM on the board. When the Stamp was reset, the PIC would interpret the pseudocode in the EEPROM and run the user’s program. In essence you had a ‘reprogrammable’ microcontroller.

The Stamp was groundbreaking for the microcontroller and educational world. I ecstatically remember the first time I blinked an LED using BASIC --- I had control over the physical world! I could do anything! Then I attempted to take a reading from my sensor and convert it into a float (floating point operations take a lot of code). Suddenly my Stamp was maxed out, and I couldn’t do any of the other functions I needed for my rowing device.

When I hit the limit with Stamps, I started to dig into how they worked. What is this PIC on the Stamp? What does it do? Ah, it’s the real brain.

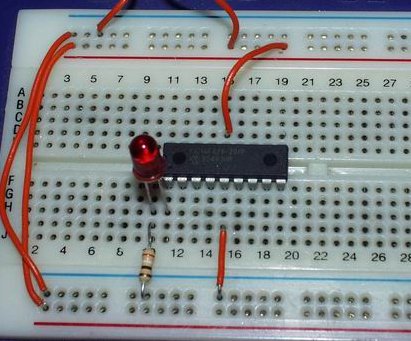

In 1998 PIC released the 16F84A. This was one of the first microcontrollers to use internal flash program memory, meaning you could reprogram the microcontroller directly without the need for an external EEPROM for an interpreter. I started to devour PIC books and the assembly language.

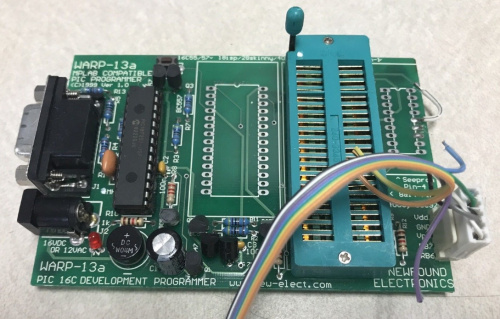

During my entire career I have written exactly one assembly program. It set up the PIC and blinked an LED. It was difficult, and when that LED blinked at midnight after two days of work I was hooked. As luck would have it I knew C, and after a bit of searching I began using the CC5x compiler to convert my C code into something I could run on the PIC. The problem was getting the code from the computer on the PIC. You needed a hardware programmer that took the compiled hex code and wiggled the pins on the micro in the right way to get the code onto it. These ‘programmers’ were often designed for production environments, difficult to find, and extremely expensive. I paid for college with student loans and two jobs. I didn’t have the money for a programmer, but after a bit of research I decided to purchase the $150 WARP-13A programmer.

This programmer enabled me to pull the chip from my breadboard or project, program new code, then transfer the IC back to my project. It was painful and often led to bent or broken pins on the microcontroller. I quickly learned about the connector at the edge of the WARP programmer. In-Circuit Serial Programming, or ICSP, was a way to program microcontrollers while they were "in circuit" --- attached to other things. This meant I could wire the programmer to my project and not have to remove the PIC each time I wanted to reprogram it. The dev cycle just got shorter!

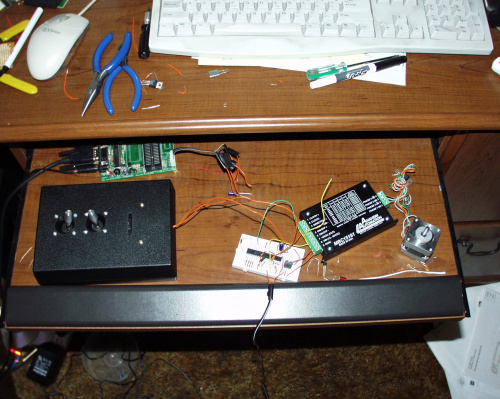

Around fall 2002, I was helping a friend at CU build a remote control for a pipe-crawling robot. Designed to inspect the inside of vertical steel pipes, the robot had huge magnetic wheels and was driven with stepper motors. My job was to translate a couple joysticks for direction and a slider for speed. I used a PIC to do all the analog-to-digital conversions (after I had recently discovered the ADC on the PIC 16F873A) and convert them to digital signals the stepper motor controller could understand. I was out-of-my-mind ecstatic, learning far more at home than I was in class.

But look at all that junk on my desk. The bits of wire and parts? You can see where this is headed. In a particularly exciting session I had the PIC reading the joysticks and the motor turning! And as I rearranged a few things on my desk, the energized programmer came in contact with a screw, or a leftover LED leg, or a bit of wire --- I’m not sure. But in a split second there was a spark, a bit of smoke, and my $150 programmer was dead.

It is when we are pushing our limits of knowledge that we are having the most fun. And when destruction or a setback occurs, it can be a catalyst for something amazing.

I needed a new programmer. I jumped on the internet and looked for the cheapest PIC programmer I could find. There were many to choose from, but a company called Olimex kept showing up in the search results. They had good hardware and very low prices, but their website was scary. There was no way to check out online and, after a few emails to place my order, I discovered they were based in Bulgaria. While I enjoyed learning about the world, I was someone without a passport and had no knowledge of Bulgaria, let alone how to send money to them.

The whole ordering process was cumbersome, hard and angst-filled. In that moment I decided to try something: Rather than order a replacement programmer, I would order a few extra programmers and bits that Olimex sold, and then I would resell them to friends at CU. I had been showing them what I was doing with my PICs, and perhaps they would catch the hobby bug that I had. Maybe I could sell these bits and pieces on the side to help feed my own addiction to projects and learning!

To do this I needed money. Let me take a moment for a public service announcement:

There’s great romance that has been built up around Silicon Valley and the concept of venture capital. If you can, avoid it. There have been numerous articles written about why (1, 2, 3), but the main thing to know is that you don’t need VC to start a company. I knew I needed to place the order with Olimex and that I needed to buy an assortment of accompanying cables and PICs to sell alongside the programmers. I didn’t have money, but I did have a credit card with a $2,500 limit. So I faxed my credit card number to Bulgaria, ordered a handful of parts from DigiKey, and went hunting for the U.S.-compatible power supplies that were needed to make the programmers work.

Over Christmas break 2002 I put together a website with off-the-shelf e-commerce software; began photographing all the programmers, cables and parts as they came in; and filed paperwork with the state of Colorado to do business. The day my programmer died was still fresh in my mind. That moment when sparks fly and you’re having fun stuck with me. The SparkFun.com domain name was available, and SparkFun Electronics was born. On January 3, 2003, I had my retail sales tax certificate from the State of Colorado, and was ready to do business.

2003: Year Zero

The first few SparkFun customers and orders have been lost to history, but I do remember my first order came in within a few hours of turning on the website. I had the benefit of Olimex listing SparkFun as a U.S. distributor of their products. There was a large quantity of people who knew Olimex and had the same hesitation I did about ordering from Bulgaria. When they saw a U.S. reseller with online checkout, they felt more reassured.

In retrospect, the business plan was so simple anyone could have done it:

- Sell stuff that people need but that's hard to get or use. For example, we sold the serial cable and power supply for the programmer as add-ons. You could buy a programmer from a few different places, or you could buy everything from SparkFun and know it would work together.

- Show multiple photos of everything. In 2002 very few online businesses had good product photos. The electronics industry was even worse; they believed customers would find photographs of electronics ugly, when in fact we wanted to see everything! I wanted to see the back of the programmer. How big is that chip? Show me a quarter next to it so I can tell! Show me the cable that ships with it. I wanted to see the connector up close so I could figure out what power supply would work with it. If I had this issue, I knew other customers would as well. SparkFun has been taking fun, weird photos (oh, Charlie) ever since.

- Provide easy checkout. It’s easy now, but in 2002 online checkout with a credit card was hard. Make it easy for people to spend money, and they will.

- Document around the hard bits. This electronics hobby thing is hard. If I hit a pitfall or barrier along the way, I would document what I learned so that others could avoid the same potholes and save time and money.

From that point on I was shipping! And ordering more inventory. And riding my bike to the post office to mail stuff internationally. Then off to campus to try to pass Linear Systems (I barely got a B-).

Ah, those were the days of CRT displays. I had everything I needed: a postal scale for printing postage, a thermal printer for printing labels and a regular printer for printing packing lists. If you happened to call the SparkFun number in those days (and I wasn’t in class) you’d get me answering the phone: “Hello, this is SparkFun.” In the rare case I had messed up your order, it was I who would “talk to Customer Service to get your order fixed, and then talk to Shipping to make sure this doesn’t happen again.” It was just me, on my bed, fixing the order I had messed up. I didn't mean to deceive; it’s the simple act of making oneself look bigger by using the royal "we." We, SparkFun, had a big website. "We" made sure it sounded like SparkFun was legit. In the end, as long as the right stuff arrives, it doesn’t matter if the brown box on your doorstep came from a gigantic shipping depot or from someone’s bedroom. But if you knew you were ordering from someone’s bedroom, it just wouldn't be a comfortable purchase.

In 2003 the stock could fit in a chest of drawers and a shelf:

Fifteen years later there’s a bit more:

It was a slog to finish up school and get my undergrad degree. In the end, the most gratifying and shocking moment was when my professors would ask, "So where are you applying to work?" I said I wasn’t applying anywhere, and in fact I was looking to hire my first employee to help me ship orders. Their look let me know that "good" engineers get a job at HP, StorageTek, IBM or Sun Microsystems (all companies near Boulder). Ah, how times have changed!

2004: Year One

In 2004 we (OK, it was still just me) were finally able to begin designing our own products. Analog Devices had released their amazing dual axis ADXL320 accelerometer. Their eval board was $450. Perfectly reasonable for industry, but shockingly expensive and out of reach for the hobbyist or student. So SparkFun released the ADXL320 breakout board in two sizes. I think we charged $40 for the larger board and a $10 upcharge for the "Tiny" version.

So many little boxes!

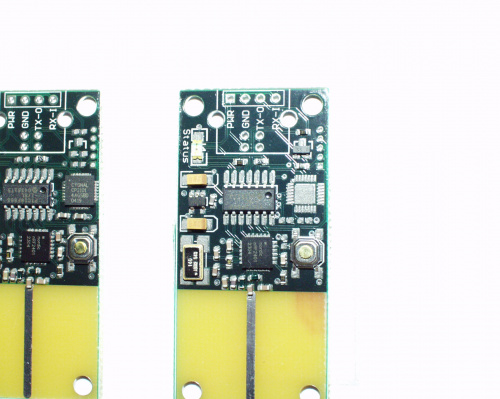

In 2005 SparkFun moved into the basement of a rental house (so much space!). We released a breakout board for the nRF2401 wireless IC. This was a big deal. The Nordic chip enabled users to send little packets of data over the air with just a few hundred lines of code.

SparkFun also released the SMiRF, or Serial Miniature RF link. This device used an onboard PIC to do all the configuration and packetizing --- all you had to do was pass serial in, and you got serial out. Note the solder paste; we had to figure out how to manufacture electronics on a shoestring budget out of the basement.

Along the way we wasted $2,300 on a reflow oven that didn’t work, and then figured out how to do Surface-Mount Device (SMD) reflow with a $30 hot plate, documenting it all along the way.

Different location, same-looking desk. Note the rotary phone in the background.

2005: Year Two

It was 2005 when we had our first tutorial go gang-busters. On a sort of an "I wonder if I could do that" bet, I converted an old rotary phone into a cell phone. We documented (getting the trend here?) how we replaced the insides with a PIC microcontroller, a cell phone module and a DC boost ringer circuit. I fondly remember buying a paper copy of the New York Times article for my mom.

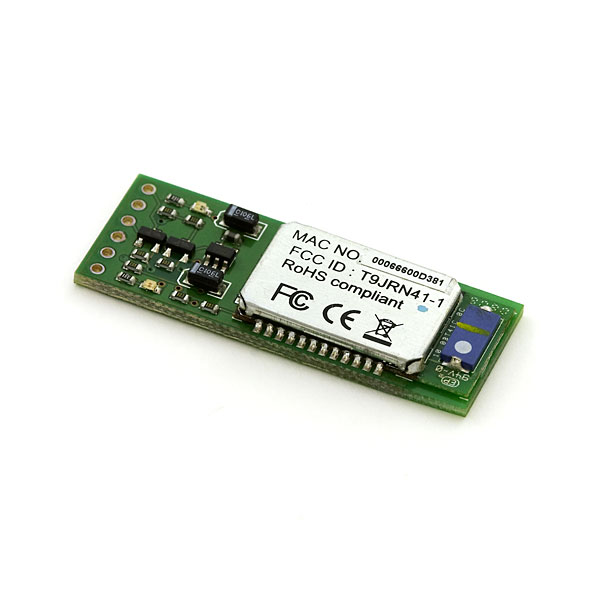

Later in 2005 we found a Bluetooth® module that replaced all the functionality of the SMiRF. The RN41 Bluetooth was $30 and required that we purchase in quantities of 1k MOQ (minimum order quantity). If I had been spending venture capital, I would have been careful with how I spent the money. But since this was my money, my debt, and the sales of this product would mean making payroll or not, the purchase of 1,000 Bluetooth modules was a watershed moment. I remember when we received the package and I realized I was holding the down payment of a house in my hands. It was terrifying and invigorating. We were very careful how we handled that inventory and that product. As it replaced the SMiRF, the BlueSMiRF became a hit, and we built units as quickly as we could.

Finally, in 2005 the sensor world was evolving quickly. Solid-state gyros were becoming available at a reasonable price for the first time. A single-axis gyro cost $50 in quantity. Combining three gyros and two dual-axis accelerometers meant you could capture an entire inertial frame. While it was terrifying to permanently solder three $75 breakout boards to a single product we weren't sure was going to sell, an IMU was a big deal. We decided to release the 6DoF (6 degrees of freedom) IMU (inertial measurement unit). Throw a BlueSMiRF at it, and you can get a wireless IMU for less than $500! This was living in the future!

2006: Year Three

We're all official!

We outgrew the basement of the rental house, and in 2006 moved to a 2,300-square-foot commercial space.

In the same vein as the 6DoF IMU, we released a wireless accelerometer and a Bluetooth device that could communicate with Roombas. Wirelessly controlling a Roomba was born! The WiTilt and RooTooth products followed shortly after.

We built a 12-foot-long GPS wall clock to show the world that GPS is really great for position (latitude and longitude) but also outputs an extremely accurate time source. It was another popular tutorial that allowed us to attend the first Maker Faire® in San Mateo and demonstrate it there.

Later in 2006 we expanded to other vacant portions of the commercial building. It was noncontiguous, but we were desperate for space. We had been building countless boards by hand, stenciling the solder paste, placing components with tweezers and reflowing in the skillet. When builds started to back up, we bought a second skillet. We later upgraded to our first real reflow oven (used), and our first pick-and-place machine (new). If memory serves me, it was ~$75,000 and took 12 weeks to arrive after a 100 percent prepayment. Ouch.

We had our first company party at the end of 2006. Not surprisingly, my friends showed up as well and gleefully ran up a bar tab of just over $1,000. It was a well-deserved break from the breakneck pace.

2007: Year Four

In 2007 we continued to expand our footprint in the building.

Inventory became an increasing problem. No longer could we use spreadsheets and dry-erase boards to keep track of what needed to be ordered. I believe it was in 2007 that we started developing our own purchasing system, which, over 10 years, would morph into the full-blown ERP system called Sparkle that we use extensively today.

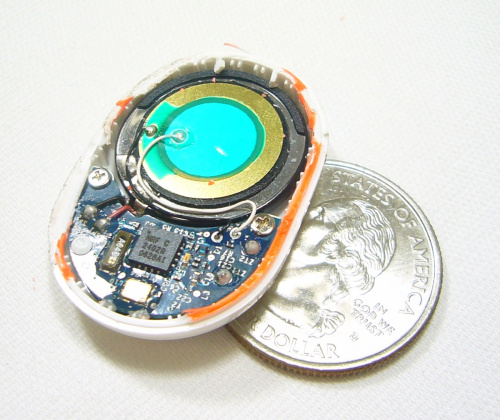

We read a paper about how people could use the popular Nike+iPod product to track people. We decided to do a teardown, discovered it used the same nRF2401 IC from years previous, and created a product that would allow us to open our Mazda without pressing a button!

In mid-2007, we completely outgrew our original building. We started looking for a new home, and in December 2007 found a space so large it echoed when we moved into the second floor of a 40,000-square-foot building.

How do you get a reflow oven to the second floor of a building with no cargo elevator? You get a bunch of people together and get creative. Luckily the pick-and-place machine could be stripped down to fit into the available elevator!

SparkFun was now located in a quarter of the overall building (about 11,000 square feet), with another company occupying the rest of the building. We had plenty of room to grow and were excited to get to it.

2008: Year Five

Then 2008 happened. While the financial sky was falling, SparkFun was doing OK. We continued to grow to around 50 employees.

At the same time, our roommate in the building (Polycom is a multinational company with multiple sites) closed up their entire manufacturing line and cleared out their part of the building. They were two years into a seven-year lease. A good portion of business is being lucky; by the end of 2008 we needed more space, and because our old neighbor was paying for space they weren’t occupying, they were more than happy to give us a great sublease deal. Did I mention we got access to a shipping dock? After five years of walking packages up and down stairs, we could finally ship things from A DOCK. It was a good day.

2009: Year Six

The start of 2009 brought the Geek Tour of China. Bunnie Huang put together a group of hackers and makers and showed us a handful of factories, as well as the Huaqiangbei (wa-shian-bay) electronics market in Shenzhen. It was incredible, and a great way to spend a week with fellow geeks. You can see more pictures here.

It was 2009 when we hosted our first Autonomous Vehicle Competition (AVC). DARPA had been running their Grand Challenge for a few years and very large, very expensive vehicles had been thwarted by a bush. Our idea was simple: We have the tools; let’s build vehicles cheaper and smaller. The fastest vehicle to get around our square building on April 15, 2009 (tax day), would win a prize.

It was an incredible turnout, complete with the fire department rescuing a downed autonomous plane. Check out the recap for some good photos.

It was inevitable, but someone finally took one of our products and did something illegal with it. Our popular BlueSMiRF was found inside a credit card machine in Canada. It looked like it was being used to transmit skimmed credit card numbers over Bluetooth to the perp’s cell phone. Thus began a good conversation on our role and responsibility as a community to teach and push people to do good with technology.

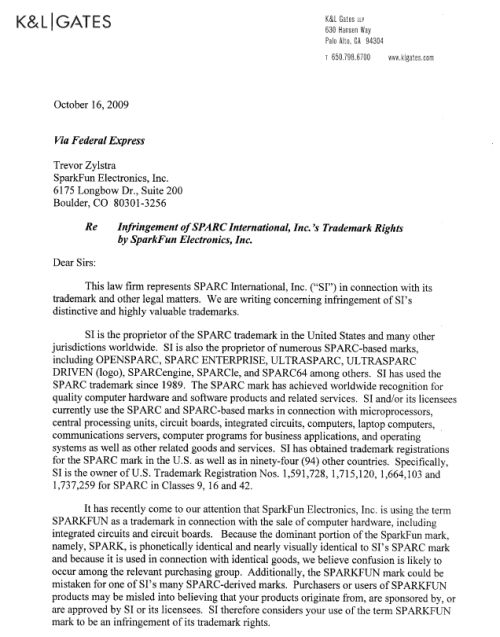

The year 2009 also heralded our first legal entanglement. We received a skinny FedEx envelope (they're the worst) from the K&L Gates law firm (they're the worst) informing us that we were infringing on the SPARC trademark. We were to immediately cease running our website and desist from using the SparkFun Electronics name. Terrified, I called our attorney, Keith.

Nathan: Is it legal to post this cease-and-desist on the website?

Keith: I don’t recommend it, Nathan.

Nathan: I didn’t ask what you recommend; I asked if it was legal.

Keith: It’s legal to post the document you received.

Nathan: OK, thanks.

We promptly posted a PDF of the cease-and-desist, and a classic David-and-Goliath battle ensued. That was a harsh lesson in intellectual property and the lengths to which companies will go to protect it. Thankfully, the internet can be a powerful weapon, and a multibillion-dollar conglomerate had to talk about a little company named SparkFun at their annual board meeting. It was amazing. SparkFun eventually signed an agreement with SPARC agreeing not to build servers based on 1990s chipsets, and they agreed not to sue us.

2010: Year Seven

To celebrate the start of 2010 (and to put our fancy new servers to task) we hosted our first FreeDay and promptly melted our fancy new servers. The lead-up to the day, coverage and aftermath was bonkers. It was a good lesson in the virality of the internet, and just how crazy people can get when you offer them something for free. To this day, I still have people who walk up to me shaking their heads in amazement and saying, “Free Day, jeesh, that was a wild one."

The year 2010 marked the second AVC and included my second entry: Elmo driving an electric roadster. After months of programming and testing, I’m proud to say Elmo completed the course.

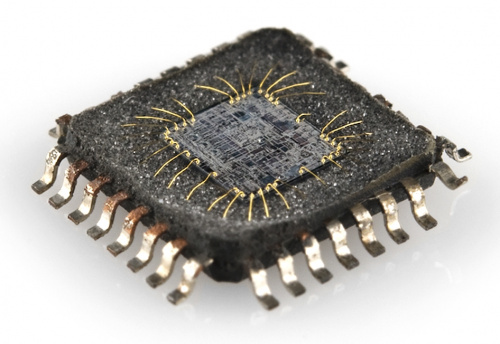

This was around the time when Arduinos were really becoming popular. Whereas the main Arduino Diecimila used a Dual-Inline-Package (DIP) ATmega328P, our popular Arduino Pro Mini and Arduino Pro used the SMD version of the ATmega328P. Atmel had not produced enough surface-mount 328s to cover the demand, and the world was feeling the crunch. We normally purchase all of our major ICs from mainstream sources (Future Electronics, Mouser, DigiKey, etc.), but because of the shortage we started poking around alternate sources, including Alibaba. We knew going into a transaction with a new, untested, slightly shifty vendor that it would probably not end well. But we were desperate, and on the off chance that we could actually get ATmegas, it would be worth it. You can probably predict that we ended up with fakes, but the process of trying to figure out what was actually under the cover of the fake ATmegas was an incredibly fun journey.

Finally, in late 2010 we agreed to rent the entire 55,000-square-foot building. What started as “11,000 square feet?! We’ll never fill that!” turned into one of the best moves we could have made. We were lucky that we ended up in a building we could so easily expand across.

2011: Year Eight

The year 2011 was a blur as we built our one-millionth product. There was a great interview with Basecamp, talking about how we had bootstrapped SparkFun.

We also had an interesting event called the Viking Funeral. This all started because I talked to Abe in production in passing. Here’s the (cough) cleaned-up version.

Nathan: Whatcha building today?

Abe: Rootooths! I hate these things!

Nathan: What? That’s my design! Why do you hate it so much?

Abe: The holes on the PCB are small and make it incredibly difficult to solder on the com cable.

Nathan: Are there other products you hate building?

Abe: Yeah, X, Y, Z, and, oh boy, this other one is horrible, and...

This was the wake-up call that engineering was not talking to production about Design for Manufacture (DFM). So I offered a deal to production: pick five designs that are really difficult to make, and we’ll have a Viking Funeral for them --- complete with fireworks --- and never make them again. The funeral forced good conversation about how to improve designs for manufacture. Eventually all five of the "funeraled" designs got revised, and future products were designed with DFM in mind.

2012: Year Nine

We hosted our first soldering competition in 2012. We had a great turnout and learned that hosting events is fun, but hard. I learned it’s a heck of a lot harder to solder when you’ve got a timer counting down and adrenaline pumping through your veins!

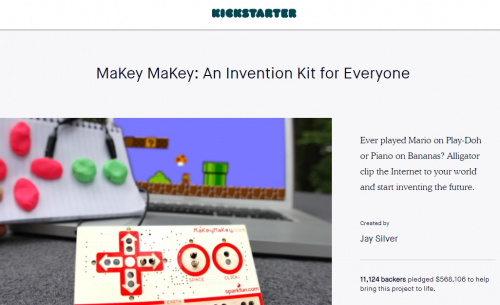

During a trip to MIT Media Labs in early 2012, Jay Silver pulled me aside to show me his prototype. If you know anything about Jay, he’s an incredibly positive force. His prototype was a Teensy with a bunch of wires hacked together, and with a pencil scratching out thick lines of carbon, he started to play a piano on paper. I was blown away. Jay and his co-creator, Eric, had a proto, but if the Kickstarter was successful they would need help designing the board, producing the product and getting the orders shipped to backers. I thought it was a great fit for SparkFun and went back to work with one of our engineers, Jim, to get the Makey Makey designed for manufacture and get our logistics team queued up. Little did we know we would be building more than 10,000 units. The Kickstarter was a huge hit, and pushed everyone at SparkFun to the edge. We were extremely proud to get the orders to the backers on time and on budget.

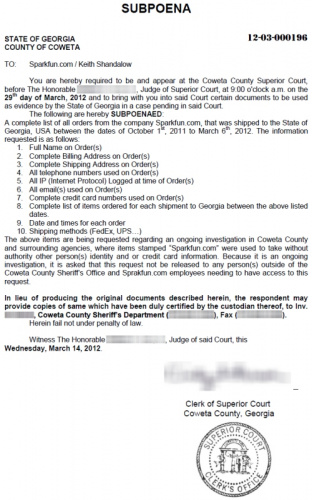

You’ve probably seen people get "served" a subpoena on TV. Usually it's a little, blue folded piece of paper. Not so in real life. In 2012 SparkFun got "served," but in the oddest way --- it turns out subpoenas can be sent via email with nothing more than a jpeg of a judge’s signature and a complete disregard for spelling. We fought hard, but in the end we had to turn over 12 names of customers (rather than 3,000). It was a wake-up call on how SparkFun should respond to future legal requests for information.

In late 2012 we developed and deployed a huge effort to do something really cool for Free Day 2013. We designed a system so that at checkout, in the background, we’d roll the dice. If your number came up, you would get your order for free. We wanted to avoid the craziness of previous Free Days while giving back to the customers who had been with us and made us great from the beginning. Unfortunately, we should have done a bit more research, as it turned out that we were probably running an illegal lottery for a few weeks. Luckily, we didn’t get in trouble, and shared what we had learned so that other folks wouldn’t make the same mistake we had. Even failures make me smile...

2013: Year Ten

As 2013 started and SparkFun turned 10 years old, we made a few moves. The first was to purchase 4.3 acres of land for the future headquarters of SparkFun. You should really read "How to Build a Building" --- it’s a wild look into how commercial real estate gets developed. Our second move in 2013 was to sell BatchPCB, a company SparkFun had started to sell the extra PCB space on the panels we ordered for prototypes. The demand for cheap PCBs had grown, and new, excellent companies like OSHPark were popping up and doing an amazing job. At the same time SparkFun was growing like mad, and we were just not able to properly run BatchPCB in the shadow of SparkFun. OSHPark graciously picked it up and has done a great job with it.

Later in 2013, SparkFun was invited to speak on copyright and intellectual property in front of the House Judiciary Committee. You know all those videos of people speaking on C-SPAN? Well, I added to that catalog of speeches. While the 4 a.m. wake-up time was a bit rough, it was a tremendous experience to see how legislation gets hammered out.

Oh yeah, there was $0 Day at SparkFun in 2013. That sucked. Basically what happened was we deployed some new code that added some small new features to the website. It worked. We all went home for the night. The next day we arrived to many thousands of orders (way more than usual), all with $0 of payment. What we found was that around midnight, the website ran the currency conversion script that it does every night (so we can display accurate product prices in various currencies); unfortunately, the unrelated feature changes caused the script to fail, and it didn’t fail gracefully. Shortly after midnight, all product began to be displayed at $0. SparkFun was quickly picked up by various "deal" websites, and a small number of people placed a tremendous number of orders. We got things sorted out quickly enough. For the customers who had been with us and ordered before, we honored their order. For the folks that showed up for a quick buck, we canceled their order and emailed them with our apologies. It was a fine lesson to learn in IT development.

2014: Year Eleven

In 2014 we had another major legal entanglement. This time with Fluke, a major manufacturer of multimeters. We had been selling a fantastic $15 multimeter for years. I found it during one of my trips to Shenzhen. I have one on my desk right now (and in my toolbox at home, and in my car...) and use it every day. It’s yellow, and that was the problem. Fluke claimed that they had trademarked the color yellow for all of their products. Note, they were not asked to specify a Pantone or color value for their yellow, just all yellow handheld instruments. We didn’t know this until 4,000 of our multimeters were seized in the port of LA by Homeland Security. It turns out small business owners bear the burden of knowing all trademark registrations currently on file. We did not know we were infringing, nor did we know Fluke took issue with our $15 DMM versus their $200 units (no one is confused between them regardless of color). In the eyes of customs and border agents, this does not matter. I believe Fluke could have allowed the SparkFun multimeters through, but instead, through a rather ingenious PR move, Fluke offered to replace the cost of our loss with their multimeters. Great, but we couldn’t sell their multimeters, and were still out of stock of the much more popular $15 meter that students could afford. All 4,000 multimeters were destroyed. It was a good lesson in how to not poke at large corporations. We changed the multimeter to gray and have kept moving.

In mid-2014 we worked with Geek Ammo, a company in Australia, to Kickstart the MicroView. This was a genius device that combined an Arduino Pro Mini, a small OLED display and a sleek enclosure. The marketing was spot-on, and the Kickstarter was a huge success. I valued it as a great product on its own, but also because the OLED display had a ribbon connector that needed to be soldered to the PCB. We needed to develop more OLED products in the future, so we needed this manufacturing capability in the building. MicroView forced us to figure that process out. Sometimes doing things that hurt in the short-term can pay off in spades in other ways.

Nothing ever goes off without a hitch, and we unfortunately shipped 2,000 broken MicroViews. They could be fixed in the field, but it required some advanced poking and prodding, so we decided to replace all 2,000 units. Man, that hurt.

The year 2014 included a wonderful trip to the White House (complete with snipers on the roof) to attend the White House Maker Faire.

Later that year we completed construction of the SparkFun building and moved our entire 55,000 square feet of inventory, machines, furniture and people to our new 80,000-square-foot home, complete with 220kW of solar power (enough for a third of our energy!).

2015: Year Twelve

The year 2015 brought about our 5-millionth widget. It’s staggering to think just what an impact we’re having on the world! To facilitate that growth, we purchased our fourth pick-and-place machine (~$300k for this one). You can see it in action here. At the same time, I found myself being pulled further and further away from building and writing, the two things that started SparkFun! So in 2015, we announced that we’d be hiring a new CEO. And thus began a slow, six-month process.

I learned a few lessons during the search for a new CEO:

- I thought building a building was risky (and it was). Hiring a new CEO is a heart transplant. It’s incredibly risky and stresses people out.

- I found help in a recruiter. SparkFun has never used a recruiter for any position in the past, but the mix of requirements and our lack of ability to reach good candidates meant we had to pay a pretty penny to get professional help. As a friend pointed out, "How will you reach the excellent candidate that is gainfully and happily employed? You can’t, but a recruiter can." In the end, the value was far greater than the cost, but it was hard to swallow at the onset.

2016: Year Thirteen

In 2016 we completed a rigorous selection process that included multiple meet-and-greets, interviews, and finally having the candidates give a presentation in front of the SparkFun employees. It was an eye-opening process that I’m glad we did. But nothing is ever straightforward...

Right in the middle of this endeavor I met with the SparkFun board of advisors. This is a group of incredibly intelligent individuals who have vast experience in many walks of life, who fly in from around the USA. They have seen and done things I can only dream of accomplishing someday. I am humbled in their presence and seek their guidance, especially at times like interviewing for a new CEO. In very direct terms I was told by one of the advisors that hiring a CEO was extremely risky, foolish, and I might as well burn the whole thing to the ground. This was devastating as we were very near completion of the interviews, and I was working extremely hard to transfer SparkFun to someone who could successfully take over. I could not continue for much longer, but to be told that I was not only wrong but dead wrong was terrible. And here’s that lesson again: Seek guidance from smart people, listen, but pick your own path. Ultimately I decided not to follow their advice, and I sadly lost them as mentors.

After all the dust settled, Glenn Samala was the outstanding person who could take on a beast like SparkFun and lead us to the next generation. He agreed to come on board in late 2016, and I worked with Glenn for months to get him up to speed.

2017: Year Fourteen

In 2017 Glenn and I brainstormed a new path for me at SparkFun, and SparkX was born. It’s basically returning to 2005 where we spin boards, products and projects as quickly as the market moves. Depending on how the product performs, SparkFun picks it up and gives it the full DFM and marketing makeover. I was a kid in a candy store again, and I think it showed. In 2017 we released close to 30 new products, including a completely new genre called HARP, or Hardware Alternate Reality Puzzle; a new interconnect system; and a flexible display. We’ve been experimenting with all sorts of new technologies and methods.

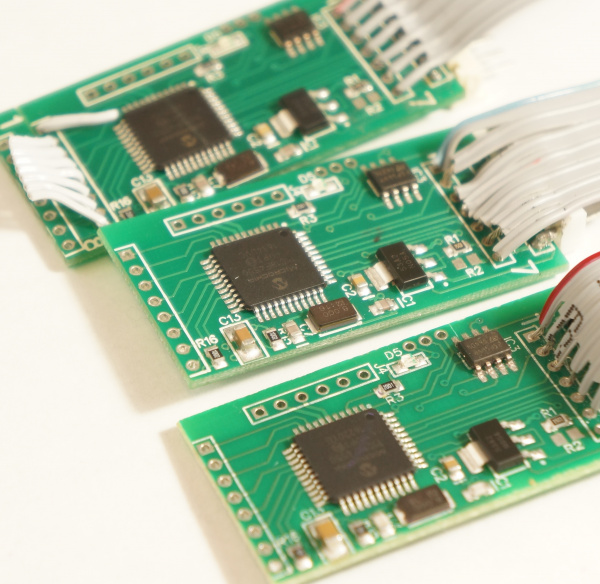

For the first time, law enforcement came to SparkFun to ask for help rather than demand customer data, and we were excited to help! SparkX was given the task of reverse engineering a handful of gas pump skimmers. We were able to decipher how criminals were using the devices, and even build a cell phone app to help detect them in the field.

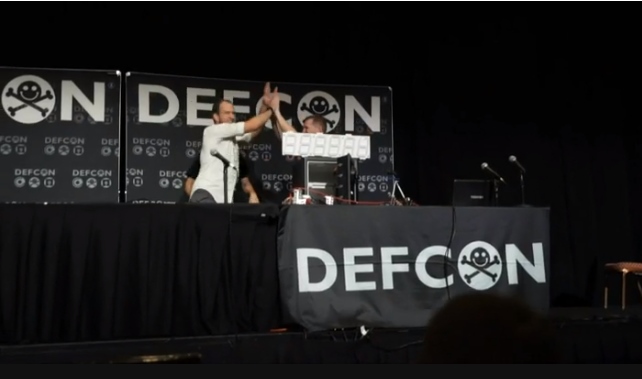

The crowning moment of SparkX in 2017 was the successful cracking of a safe on stage at DEFCON in front of 800 people. We purchased a fire safe in Las Vegas (because who wants to fly with a safe?), cut open the box on stage, set up the robot, and I gave my presentation about the vulnerabilities we found in order to open the safe in under an hour. It was one of the most difficult presentations I’ve given, simply because there was a device 10 feet to my left making noise and not opening the safe!!!. It wasn’t until around minute 31 that the robot successfully opened the safe. It was terrifying, thrilling, and something I will remember for the rest of my life. The BBC did a great video about the safe-cracking robot. You can read the full tutorial about how we built the robot as well.

A summary of lessons across 15 years:

- You don’t need venture capital to be successful; 99.9 percent of companies don’t have VC. Bootstrapping is hard, but the benefits can be much more valuable than investors.

- Start a company when you're young. It gets harder later in life when you have more responsibilities.

- Pick one thing and nail it. SparkFun doesn’t do consulting or contract manufacturing; we just design and manufacture cool products for people who are excited about building electronics projects. For a bonus, pick a business that you’re incredibly passionate about. It will help when you’re working late on a Saturday night for the 10th time.

- The same people who say "that will never work" are the same people who haven’t tried everything. Listen to good advisors, but choose your own path.

- People will spend money with the company that has the least transactional friction. Initially, SparkFun did not have superior or original products (DigiKey had a far larger catalog, we just resold Olimex’s stuff, etc.). But SparkFun offered multiple photos of the product (DigiKey had no photos back in the day), and we had online checkout (Olimex required that you fax your credit card number or send a wire).

- You're going to mess up. Cop to it, explain what happened, and move on.

- Take lots of pictures along the way. It can be a wild ride; don't forget to stop and take it all in.

And Beyond

It’s times like Christmas Eve when I’m working, the building is completely empty, and I get a chance to walk around and take a moment to just absorb the magnitude of the situation. It’s staggering. It’s been 15 years. The highs are extraordinary, and the lows are deeply wrenching. Against all odds, I believe Glenn and I have managed to hand off SparkFun successfully. He’s enjoying working on the business problems at SparkFun, and I’m enjoying working on the product problems at SparkX.

Where are we headed? Well, since I’ve already made a fool of myself, I’d love to pontificate on the future! Here are a few predictions that may or may not come true...

Five years from now the global demand for electric vehicles and large bets like the Gigafactory will drive the price of batteries to wacky levels. Solar, wind and storage will compete directly with the cost of energy generated by fossil fuels. I’m excited to see the debate and denial of climate change dissipate into a discussion about market forces. We’ve seen the natural gas boom uproot the coal industry. I believe a mixture of capitalism and ingenuity will push us further toward cheaper, less environmentally costly energy.

Autonomy (mostly vehicular) will drive the price of LiDAR, sensors, image processing and AI down. We will see the complexity of autonomous-enabling technologies that are currently only accessible to field experts become boiled down to the point where mere mortals can utilize them. Cheap cameras and OpenCV (computer vision) have made it possible for hundreds of consumer products to make decisions visually; the same will happen with complex, autonomous-sensing frameworks. I’m probably going to lose the ongoing autonomous car bet I’ve got with my wife (can I buy a level-five-capable autonomous car from a public car dealer before 2022?), but it will be so worth it when I don’t have to drive in traffic.

Cell phones will continue to push ever smaller footprints of components and the integration of sensors. We’ve seen powerful processors combined with accelerometers, gyros and magnetos into smaller and more powerful ICs. We’ve seen new air-quality sensors being packaged so as to be built into the next generation of phones. The ESP8266 ripped a fantastic hole in the WiFi market --- there will be many more upheavals. I hope to see more dark horses like Espressif give some of the entrenched players a run for their money. We’ve joked about the AllDoF for years, but the next five years will continue to march toward ICs that have more sensors and more processing capabilities, with easier and more streamlined programming interfaces.

Happily and thankfully, the next generation of students will learn how to program and work with technology. Not because this world needs more EEs, but because this world desperately needs more technical citizens who can lead and govern with a footing in more of the layers of what makes our great civilization work. A record number of students will graduate high school with more computer science and technological exposure than ever. And most importantly, they will be comfortable obtaining new knowledge through whatever platform or channel is the best. Where people like me have to be reminded to search YouTube about how to fix the furnace blower, my young niece will scream through a six-month primer on whatever language or methodology she’ll need for the job she scored half a world away.

Thanks for reading and sharing in some of these crazy adventures. Let’s hope the next 15 years pack as much bang as the last 15.

---Nathan