VCSELs and Distance Sensing

How do you build a better laser? Maybe this way.

In order to see stuff, electronically or otherwise, you have you have to first bounce something off of the stuff you want to see, then wait for some of what bounced off to bounce back at you. Then you do some math and figure stuff out. To figure out a distance from our eyes, the math stems from having two cameras at known angles. And while we can duplicate that function electronically, we more frequently use only one sensor and calculate based on known velocity of the something we hurled at the stuff we wanted to see at the time of hurling.

So, what if something is there that we can hurl at a known velocity? Well, we’ve tried rocks, and then very small rocks (it’s left as an exercise for the reader to prove why rocks are a bad choice)… but what works way better than rocks is sound because it always travels at a more-or-less known velocity. And what works way better than sound is a laser because it’s faster, less susceptible to atmospheric disturbances with much greater range, more accurate… the list goes on. In the field of range finding, lasers feature prominently. But the expense of the laser itself, among other things, has kept laser-based range finding devices relatively expensive compared to sonic varieties.

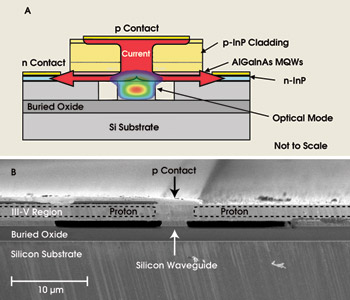

Typical laser diodes are called "edge emitters" because of the structure of the silicon that comprise them, as shown below.

What you're looking at above is a somewhat generalized cross-section of a hybrid silicon laser, which is what you'd typically find in a laser diode. While you (and I) may not have the physics background to grok all that you see there, the big takeaway here is that the optical output is on the edge of that pile of layers, thus edge emitting, and the output waveguide isn't accessible until the silicon is cut to expose it. For that reason, large-scale production and testing can become problematic.

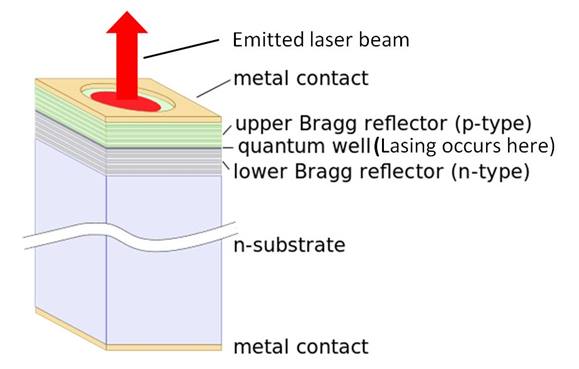

An alternative is to make what's called a VCSEL, or Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Laser. In a VCSEL, the laser output is orthogonal to the surface of the silicon, as shown below.

In a nutshell, the lasing action happens in the quantum well between two distributed Bragg reflectors (DBR). The top DBR is slightly less reflective than the bottom, releasing light from the top when it achieves enough energy.

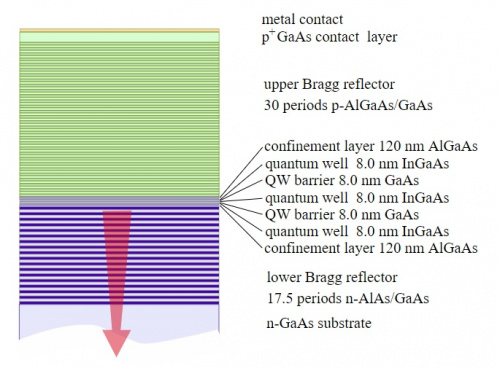

Comparing the two technologies with regard to manufacturability, the VCSEL diagram is deceivingly simple. Making edge emitters is a pain because it involves grafting two wafers together for 12 hours, as well as the previous point that you can't test them until you're virtually done with all the labor to make them. But the VCSEL device is comprised of many, many layers that have very tight control tolerances.

Courtesy of Wikipedia, that's an exploded view of a bottom-emitting VCSEL you see above. But as you can see, there's nothing simple about the internal structure. As far as difficulty in manufacturing either of the technologies, it might be a wash between the two (I welcome commentary on this point).

The really awesome thing about VCSELs is that because they're vertical, you can put a zillion of them on a single wafer, offsetting some of the process cost. You can also test them before you go to the extra step of busting them out of the larger die, potentially saving more time. Plus, you can also get some really cool 2D laser arrays (that should make any nerd drool).

VCSEL's aren't particularly new technology, conceptually dating back to the 1960's. They tend to be found in low-ish-power applications, but that's not a hard-and-fast rule. They can be readily found in lots of fiber optic stuff, computer mice, laser printers, and of course ToF (Time of Flight) range finding circuits - we currently sell a couple of varieties that are based on VCSEL technology.

If you want to up your laser game, VCSEL or otherwise (and who doesn't!), check out these additional resources:

https://www.sparkfun.com/news/2796

Interested in learning more about distance sensing?

Learn all about the different technologies distance sensors use and which products would work best for your next project.

Take me there!