Dear ON Semiconductor

We unleash the professionals at Atmel to inspect the insides of our defunct ATmega328s. We found ON Semi written inside. Tim gives us a tour of the Failure Analysis labs at Atmel, Colorado Springs campus.

Dear ON Semiconductor,

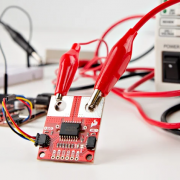

I'm afraid I have a reel of your ICs, but they have been mistakenly mislabeled. Could you please let us know what ICs these are? Here is the wafer identifier:

Marked with a label 'AG20 01 - 7'. And if it helps, this is what the entire wafer looks like:

These dies are encapsulated into a TQFP 32-pin package. We'd really like to find out just for curiosity's sake. Please email spark@sparkfun.com. Thanks!

Sincerely,

Nathan Seidle

If you've been following the saga of the fake Atmel ICs, you know what's going on. If not, read back in time a bit: ATmega Slugs and X-Rays. So a few weeks ago, our writer Chris walks into my office and against all reasonable odds of coincidence in this world, Chris lets me know that his very own father (Tim) works in the Failure Analysis labs at Atmel. What? Really? Where? In Colorado Springs about 2 hours away. You're kidding?! Tim had kindly offered to have us come through the lab and analyze the ICs for us.

Atmel is a large, international company with a decently sized wafer fabrication facility in Colorado Springs. There's a good chance that some of the very ATmegas we use on our boards could have been fabricated there! The wafer fabrication area sometimes experiences processing or testing failures. The failure analysis group is there to evaluate problems and discern how the problems were caused. But their 2nd job is to help customers when a part fails in the field. Counterfeiting is extremely rare, but not unheard of. Luckily, the processes to do fault analysis are similar to counterfeit analysis - AKA popping the top off and looking inside.

So a contingent of SparkFun geeks headed down to Colorado Springs on a road trip with a reel of ICs under our arm.

We met Tim in the lab. He showed us the various tools they use for analysis: microscopes, scanning electron microscopes, a laser to heat a single transistor junction, toys, toys, and more toys. We were in awe.

The SEM with probes is capable of taking a reading from a single NPN transistor junction.

A close up of the probes. Each probe head had a rough tip radius of 0.25 microns. That...is small.

"Xena" and "Hercules" are the two SEMs in use. They have the ability to scan down to around 10nm. Check out the monitor - this SEM is set to accelerate the electrons toward the sample with 2,000 volts!

After the much-too-short tour, Tim threw on his protective gear and started dissecting the "ATmega328."

Here's what we learned: 90% fuming nitric acid at 150C is the key. The "fuming" part of the nitric acid makes it attack organic material (namely the packaging) while leaving the inorganic material (the IC chip itself, including the bonding wires). We believe our first attempts at decapsulation went so poorly because we used concentrated nitric acid instead of this fuming nitric. This stuff is not cheap! ~$250 for 500mL, but you really only need a few drops. Heat the IC on an empty glass petri dish. Add one drop of fuming nitric acid. Let it sit for 4 or 5 seconds, then wash off with acetone. Don't try this at home! This combination of acid and a solvent is potentially very dangerous. We let the experts handle it, but really - not a good idea for the home chemist!

The small drop of acid quickly devours anything near by and then becomes used up. To wash the nitric acid away, you could use water. But combining fuming nitric acid with water, it turns into regular nitric acid that then begins to eat away at the inorganic materials (like the silicon we're trying to protect!). So Tim uses acetone to quickly neutralize the acid. Now for those astute readers/chemists, you will know that combining a strong acid with a solvent, you get a very exothermic reaction. This is dangerous and should not be attempted outside of a laboratory setting. Very small amounts of nitric acid are used to minimize the exothermic reaction to maintain safety. Again - don't try this at home.

Wash, heat, add drop of acid, repeat. This process took only 2 to 3 minutes. Tim had obviously done this before.

CMac (Chris on the left) and Nate (me on the right) hang back and watch the fun from a safe distance.

After a few short minutes, Tim had the top of the IC expertly removed. He then added the IC into a small bath of "NMP" (another smelly solvent) and then into the ultrasonic cleaner for 10 to 15 seconds. The capsulating materials contain small glass beads that enjoy sticking around. This cleaning knocked lose any residual fragments of the packaging that may have been sticking to the chip or bonding wires.

We then got to view the uncovered IC under a microscope. We immediately saw the ON SEMI markings that re-affirmed our suspicions. There's something in there, but it's not an ATmega328.

There's the give-away marking from ON SEMI. Now if you know anyone at ON Semiconductor, we'd really like to hear from them. It's going to be tricky to identify these without their help. AG20 is quite clear, but 01-7 could be anything. After talking with the folks at Atmel, each company has their own very proprietary naming nomenclature for the wafers. Who needs to know it anyway? No one ever sees anything but the label on the outside of the package, right?

The various failure analysis detectives within the office commented on how old the technology looked. They estimated the wafer to be between 5 and 10 years old. ON Semiconductor was started in 1999 so they can't be much older than that.

According to the package markings on the right, the fake ICs were produced in the 23rd week all the way back in 2007. To put the date code question to bed, we also received some information from the production facility that first produced the ATmega328s. This is what they said:

The ATMega328 was first taped out toward the beginning of 2007. Following an evaluation phase, it went into volume production toward the end of that year. It is very unlikely that there were any parts from earlier in 2007.

The date codes for December 2007 product should have been something like 0748, 0749, up to 0752. I think the date code on the counterfeit parts was 0723 which means fiscal week 23. Sounds like this would be prior to when this part went into any type of volume production, just like the test guys suspected.

So it turns out we really did receive counterfeit ICs (we decapsulated three ICs with identical results). It's not hard to see how this could happen. The going rate for the ATmega328 TQFP is somewhere between 2 and 3 dollars each. Someone had some extra/scrap ICs sitting around in the same TQFP package. Every IC gets a laser etched identifier, in this case it was just the wrong label, (intentionally wrong in order to defraud us, but the laser doesn't care), and wammo! You've got your very own ATmega328P-AUs.

Thank you Tim and all the folks at Atmel! The tour of the wafer fab and the huge campus that Atmel has down in the Springs was really amazing to see! Please come to SparkFun some day so we can show you your very own ATmegas in use.

If you read this post and find anything out to help us identify these ICs from ON Semiconductor, please let us know! We're still hoping to turn one on someday, whatever it may be...

Be sure to read the original post, the follow up report, the discovery of what's inside and the final identification of the IC!