Your Personal Black Box

Inexpensive sensors and storage are giving us the ability to record our lives, revisit the past, and sometimes solve mysteries.

It's a cliché to say that electronics are changing our lives, but some of these changes will be especially profound. We're already used to using smartphones and other gadgets to record the special occasions in our lives (and the funny things our cats do). But with sensor and storage costs plummeting, we're quickly moving towards devices that will quietly record our lives 24-7, just like the black boxes on aircraft and other vehicles. The privacy and security concerns are significant, especially if someone else is doing the recording (or if you're recording someone else). But if you're in control of the data, you'll be able to revisit the past in ways that have never been possible before.

Sadly, most black boxes aren't actually black. Via Aviation News

A recent New York Times article tells the story of two cyclists who were able to investigate their own bike accidents, even when one of them had blacked out from his injuries and couldn't remember anything about it. They were able to do this because they were using the latest generation of cycling computers, which continuously record speed, cadence (pedal RPM), GPS position, and even heart rate to allow you to analyze your ride afterward. This is great data to have when training, but it's even more useful when the unthinkable happens. One of the cyclists, Ryan Sabga, was hit by a car while riding in Denver, which the driver denied. Ryan was able to reconstruct the accident from the data in his Garmin bicycle computer, which led to the driver's insurance company paying his claim. He says on his blog that he won't ride without a "black box" again, and recommends that all cyclists do the same.

This trend is increasing. We've seen similar devices that continuously record OBD-II or video data from your car, so that if you have an accident, the data will help in court or with insurance claims (note that this goes both ways!). In fact, it's possible that this functionality is already built into your vehicle's computer system. Digital audio and video recorders increasingly have "continuous record" features, which allow you to leave them running in case something spectacular happens. The Livescribe pen continuously records both audio and your handwritten notes for later downloading to a larger computer. And as always, "there's an app for that," with smartphone applications for all kinds of black-box purposes, such as monitoring your sleep patterns.

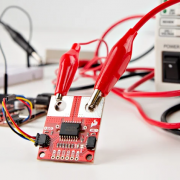

Anyone familiar with SparkFun knows that we love dataloggers. The uLog, OpenLog, and Logomatic are ideal for pairing with various sensors, and the Package Tracker (currently undergoing revision) is effectively a personal black box in itself; recording GPS and environmental data to a SD card for later analysis. Enabling continuous recording on these devices (deleting the oldest data when the memory is full) is only a matter of programming. If accident data is what you're interested in, you could even program the logger to stop recording shortly after a major acceleration shock etc. to prevent losing the "interesting" data later. This is technology you can use now, not the mythical "five to ten years" from now.

But the next generation of devices will be very interesting. Imagine wearing a device that will let you treat your life like a TiVo™, allowing you to "rewind reality" whenever you miss something or want to take a second look. We've been steadily moving towards this goal. In 1945, Vannevar Bush imagined a machine called the "Memex", which would record one's lifetime of media and communications, and "which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility." Computer science pioneers Douglas Englebart and Ted Nelson expanded on this theme, eventually leading to the hyperlinked structure of the world wide web. In the early 2000s, then-MIT grad student Brian Clarkson attempted to continuously videotape his entire life. His panoramic audio and video recording backpack captured such moments as the first time he met his girlfriend (who apparently wasn't scared off by all the hardware Brian was wearing). The 100 day experiment resulted in 500GB of data... a lot back then, but much more reasonable today. His backpack, which contained five cameras for 360º recording was a bit cumbersome, but it won't be long before Moore's law and the economies of mass production make this device pocket-sized and entirely practical. Clarkson envisioned a device he called a "familiar," which would sit perched on your shoulder, watching and listening to everything you do, building a multimedia diary for later "reality mining."

The hardware to do this is pretty much ready today. The real problem won't be generating and storing these vast amounts of data, but providing useful access to it. An active research area is automated indexing, allowing you efficiently search for the needle of information you want without having to manually tag everything in your digital haystack (this is bad enough with an MP3 collection, much less your entire life). The ultimate familiar would use AI to not only record, but analyze what it sees, letting you ask it simple questions about the past, rather than having to manually rewind to an event to review it.

The ability to access any moment of your past will have a profound impact on our lives. Will this be useful, or dangerous? Will it make us smarter, or dumber? How will you apply this technology? For me, it would be nice to not have to write anything down (just go back to that meeting or conversation), and be able to retrace my steps to see where I left my keys. Better yet, I'll just ask my familiar where I left them.

Get ready to rewind!