IoTuesday: 5 Easy Ways to Secure Your IoT Devices

Got an internet-connected device as a gift? Let's have a quick chat about how to prevent another Mirai botnet attack.

On Friday, October 21, 2016, hackers unleashed a torrent of web requests at the Domain Name System (DNS) services managed by Dyn. By continually slamming these DNS servers with web traffic from different sources (known as "distributed denial of service," or DDoS), legitimate requests to get the IP addresses of popular sites like Twitter, Pinterest, Reddit, etc. were denied. What made this attack interesting is that the attackers relied on botnets (internet-connected computers that automatically communicate with each other to coordinate efforts) made of mostly IP cameras, home routers and printers infected with the Mirai malware.

- Smart TVs

- Cable receiver box

- Video game systems

- Thermostat

- Smart light bulbs

Mirai scans for connected Internet of Things (IoT) devices running some form of embedded Linux, including routers. It then attempts to "log in" to the device using some 60 known factory default usernames and passwords. Once in, Mirai infects the machine, turning it into a "bot" for use by the attacker and continues scanning for other connected IoT devices. The source code for Mirai was released in October. You can read about it here, but just be careful about clicking on random hacker site links.

With a knowledge of how Mirai did its dirty work, we can recommend a few ways to secure your internet-connected things to avoid becoming another bot on the net.

1. Unplug It

The best possible safeguard against hackers is to simply not have the device available for them. This means disconnecting it from the internet or, even better, turning it off completely. Unfortunately, this isn't always an option for some devices, like routers, that need to be on in order to blanket your home in warm, fuzzy internet access.

Here's a project idea: use a large button to control power to your router. Smash it when you get home or wake up to get internet and smash it again to turn it off when you leave. Maybe not the most convenient, but it denies access to your router (and, subsequently, the rest of your home network) when you're not using it.

2. Power Cycle

Another interesting aspect of some malware like Mirai is that it only lives in volatile memory (e.g., RAM). That means simply turning off the device and turning it back on again will rid it of the malware. Like the giant network kill switch from #1, you could make a simple microcontroller project to cycle the power on your IoT device every so often.

While that sounds great in theory, the problem is that your device is likely to get infected again within minutes, according to some reports. You're better off with a more permanent solution, like changing your default username and password.

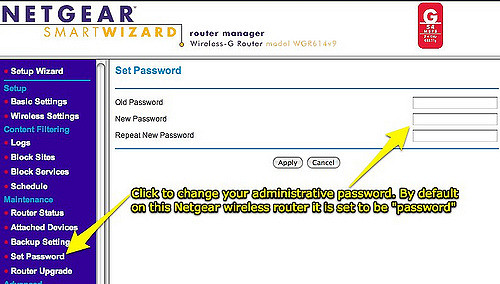

3. Change the Default Password

Seriously, if you do only one thing to secure your device, do this. It only takes a minute, and if everyone did it, Mirai would die pretty quickly.

Most home routers come with a default username and password like admin/admin or root/[no password]. Similarly, most internet-connected cameras have a web page that you can access to change such settings. If you are feeling particularly security-prone, go ahead and change the username too.

Oh, and please use a strong password. That'll help when the new-wave IoT malware hits, attempting to crack your device using a dictionary attack.

I know some security people out there will yell at me, but I like to keep my username and password for my router written down on a piece of paper near the router (because I can never remember it). It's better than having it stored in Google Drive, and if an unfriendly hacker is in my house, I have bigger problems.

4. Update Firmware

Mirai and other similar malware hope that you've left your password set at default to work. However, it won't be long before we start seeing attacks that target IoT services and open ports as potential means for intrusion.

With more traditional operating systems, like macOS and Windows, users are regularly prompted to install updates that patch security holes. Many IoT devices left this feature out; they won't automatically check the manufacturer's site for new firmware updates. As a result, you, the user, are left to manually update whenever you see fit, which could translate to "never."

As smaller devices become more prevalent in our internet-connected world, they will become increasingly more interesting targets for hackers. Finding and fixing security holes is a never-ending game of cat-and-mouse, but you can stay ahead of the curve simply by checking for new firmware on a regular basis.

Want another project idea? Write a script that checks for new router firmware, automatically downloads it and sends you an email with it attached, reminding you to update your router.

If you really want to dig into the weeds, you can try running custom firmware on your devices (assuming they support it). For example, I'm a big fan of dd-wrt. In theory, these alternatives give you increased control over security options, but they often have a much steeper learning curve.

5. Disable Universal Plug and Play (UPnP)

The idea behind UPnP was good: allow devices on your home network to discover each other, communicate and share files. However, it introduced so many holes that many security professionals recommend turning it off entirely.

The biggest security flaw in UPnP is that programs inside your network can automatically request port forwarding from the router. If one device on your network becomes compromised, it can open up ports to allow other malicious traffic to flow in and out of your network. This could leave computers and IoT devices in your network vulnerable to attacks from outside your network.

Luckily, fixing this is simple. While you are logged into your router (presumably changing the default password), look for a page with the label "UPnP" and disable any UPnP services. Unfortunately, doing this means you will need to learn how to manually forward ports, especially for things like online games.

(Update) Bonus: Disable Telnet and SSH

As pointed out by Member #398082, Mirai actually did its dirty work by trying to access a device through Telnet or SSH using default credentials. Changing the username and password in the web interface may help, but it doesn't necessarily guarantee that the the Telnet and SSH credentials get updated. If you can (likely through the same web interface used to change the password), disable Telnet and SSH services. If you can't, well, you might want to consider trading in the device for something more secure.

Being aware of potential security vulnerabilities in your network, especially as we begin to see more IoT devices hit the market, will help keep your devices from becoming the next zombie in a hacker's botnet (as well as keep your information safe!).

What other network and IoT security tips can you think of to help prevent another Mirai-style DDoS attack? Please share your ideas in the comments below.