Death of an E-Salesman

Our classic electronics surplus stores are disappearing. Can they be saved?

Those of us who are fans of electronic surplus stores (some might say "cursed") -- those Lost Ark Warehouse-like institutions filled to the rafters with all manner of technical detritus that somehow avoided the landfill, were recently saddened to hear that Weird Stuff Warehouse, a Silicon Valley institution for the last 32 years, had closed for good.

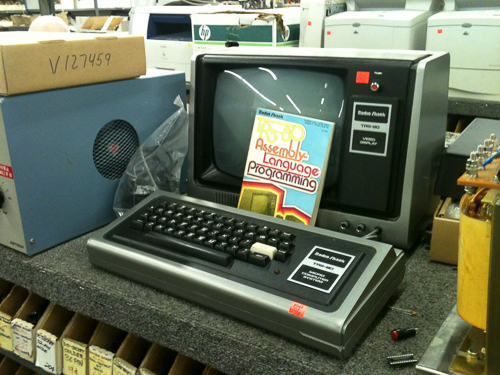

If you've never visited Weird Stuff Warehouse (or one of its brethren), imagine a sprawling metal building in an industrial park, filled with room after room and rack after rack of... everything. It's almost pointless trying to describe the range of hardware (and sometimes software) that you'll run into in a place like this. Stuff that was state-of-the-art five or ten or twenty (or more) years ago now being sold for pennies on the dollar, with the more impressive items (remember that half-sphere Mac? The TRS-80? The Juicero?) occasionally set out in museum-like displays.

This is the sort of place that you'll either love or hate. If you have a bent for making, if you appreciate the art of engineering, if you're a technology nostalgia buff, or are ecologically-minded and appreciate that this hardware might still serve a purpose, you'll probably wander the aisles with a dumb smile on your face. If, on the other hand, you eschew clutter, dirt, and especially "trash," this may be your worst nightmare. I've often wondered if any first dates took place at Weird Stuff Warehouse - one would find out very quickly whether there was any potential for a relationship or not.

Similar institutions are located around the country (and the world), their names spread in forums and by word of mouth. I'm sure I'm not the only one who makes pilgrimages whenever travel brings me into one's vicinity (usually followed by a hasty trip to a UPS Store, if the bomb-like tangle of wires I bought wouldn't make it through security). Their names are legendary: HSC Electronic Supply, also in Silicon Valley; OEM Surplus in Colorado Springs; Norton Sales in North Hollywood, unusual for its collection of not-for-sale aerospace parts that they rent out as movie props; Skycraft Parts & Surplus in Orlando, and more that I'm sure you'll tell me about in the comments.

But unfortunately, and perhaps inevitably, these stores are disappearing. In addition to Weird Stuff closing in April, we lost our beloved JB Saunders here in Boulder a couple of years ago, and the legendary four-acre Black Hole in Los Alamos closed in 2012. I'm sure many of you have similar stories. Every time I visit one, I ask them how they're doing. The answer is usually a resigned shrug: "we're doing our best."

One does not start, buy, or even work at such a business for the big bucks. One must have a deep and somewhat quixotic dedication to keeping nominally-functional stuff out of the landfill, and getting it into like-minded arms. Seventy-two-year-old Chuck Schuetz started Weird Stuff Warehouse because he felt that it was "a crime" that so much brand-new (and yet somehow "obsolete") Silicon Valley hardware was ending up in landfills.

These businesses are very hard to keep running. In fact, despite the closures, it's probably more impressive that so many are still in operation. Right from the start, the real-estate footprint is significant; often located in high-tech neighborhoods where the market is booming, putting pressure on building owners to sell. This was the fate of Weird Stuff Warehouse: Google purchased the entire area for a new campus.

Stocking electronic components is also tough. There are literally millions of actively-produced electronic parts, and many more obsoletes. It's difficult for a brick-and-mortar store to keep more than a few thousand SKUs in stock, and very expensive to keep parts on hand (think every resistor value) that may never get sold. The internet has also revolutionized parts buying - it's hard to justify the time spent poking through parts cabinets, often to find the value you need missing or out of stock, when DigiKey and its competitors let you instantly search through tens of millions of parts that they can get to you the next day if desired.

Stocking surplus equipment is even tougher. One can buy truckloads of old electronics at scrap-metal prices (that's usually how it comes). But cleaning*, testing*, cataloging*, (* optional steps), and displaying it, all in the hope that someone who needs exactly that item will somehow find and buy it, is a tenuous business model at best. Every item on every shelf is a gamble that someone, someday will want it, bet against the space it occupies, costing you money, forever. If you eventually have to scrap it anyway, you'll be faced with e-waste fees that you assumed when you purchased the item. It's not easy.

And as Sturgeon's Law would suggest, a lot of what's on these shelves is junk. Looking through stacks of formerly state-of-the-art equipment, it's tempting to think that an old router or industrial PC might still be of some use. But Moore's Law is an remarkable thing, and the pain you'll subject yourself to trying to make use of a 10Mbps router or 300MHz CPU makes this a difficult proposition at best. Unless the hardware in question is of historical value (I'm pretty lose with that definition myself) and therefore a labor of love, it's ironically almost always cheaper in every way to buy something newer and faster.

But there are treasures here that transcend functionality. Beautiful dial meters from the analog age. Gorgeous Silicon Graphics and NeXT machines that were designed by artists. Civil Defense Geiger counters, overbuilt to survive the apocalypse so they still work great, if you can find the weird batteries they run on. And my favorite - old HP and Tek test equipment, thoughtfully designed for easy servicing, unlike almost everything today.

Not to mention things that were prohibitively expensive when they were new, but offer tantalizing possibilities now: hydraulic cylinders, gigantic capacitors, GHz satellite dishes... Warning: you may get ideas for irrational projects while wandering these aisles. And if you accidentally speak those thoughts out loud ("human-carrying Strandbeest!"), you can be sure that everyone nearby will smile and nod.

So is there hope for these lost-cause monuments to tech boom and bust, full of things few people love and fewer really need? Or are they destined to close one by one as their property value increases beyond the decreasing demand for what lies within?

For specific needs, the internet has already won. Once you've gotten used to the convenience of DigiKey or the price of, well, Monoprice, it's hard to imagine going back to endless digging through bins, followed by rethinking your project to accommodate what you actually find.

But for sheer experience, nothing beats wandering the aisles of one of these places, and for that they deserve our support. Frequent them if you live nearby, and include them in your travel plans if you don't. Buy something while you're there; they'll thank you for it (and mean it). You probably won't find what you need. But I can promise you you'll find something that you love.